Why Is Antarctica So Cold? A Guide for Explorers

To understand why Antarctica is so cold, you have to realise it’s not just one thing. It’s a powerful combination of natural forces working in concert: an immense landmass at high altitude, a vast reflective ice sheet, its position at the bottom of the world, and its isolation by a powerful ocean current . This is not trivia; it is the fundamental intelligence that informs every decision an explorer makes on an expedition.

The Coldest Place on Earth

From the Fjällräven base layers you choose to the daily routine of melting snow for water, understanding the mechanics of Antarctic cold is the first step towards operating safely and effectively. It’s the difference between merely surviving and actually performing. This guide will break down the science behind the cold, providing the practical knowledge needed for any serious polar journey.

We'll explore the key factors that create the most extreme environment on our planet. Think of it not as a list of separate reasons, but as interconnected systems that amplify each other. This is foundational knowledge for any successful expedition.

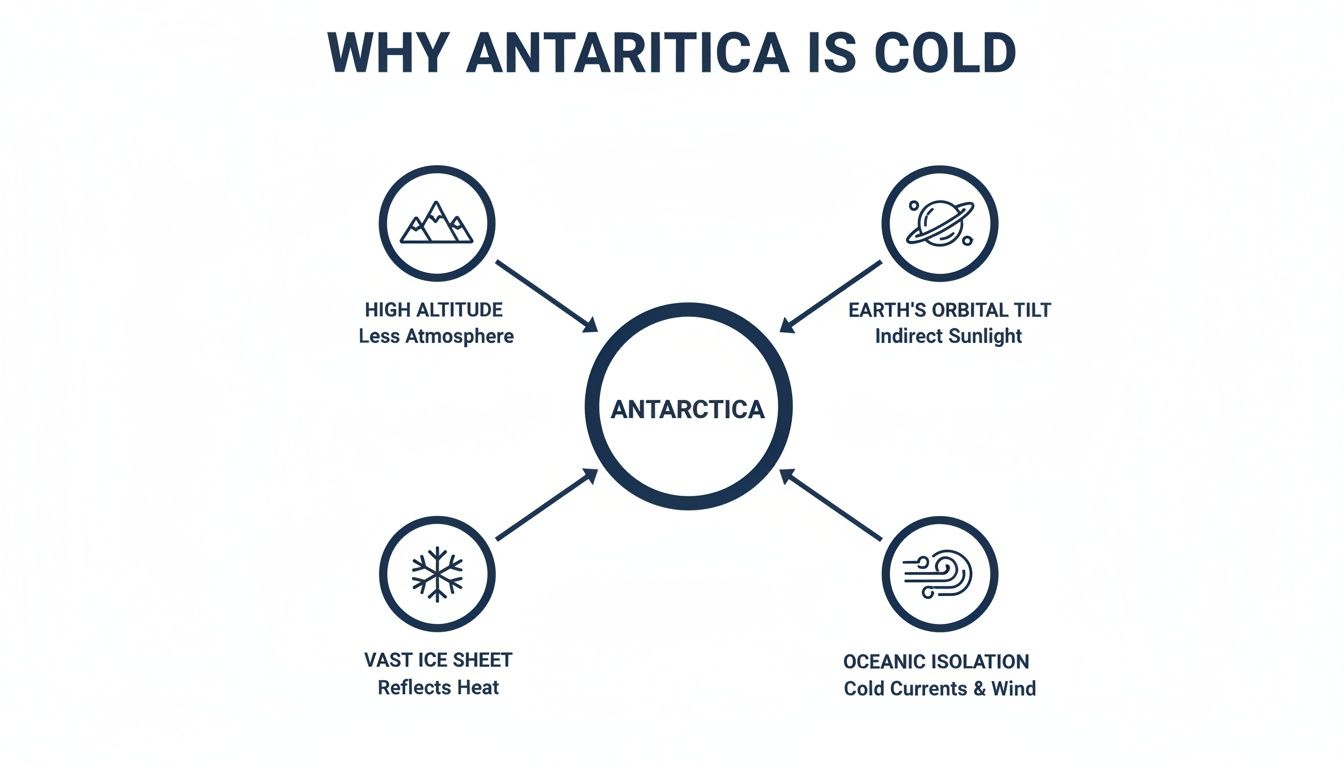

This diagram shows the four primary factors—altitude, Earth's orbit, the ice sheet, and oceanic isolation—that feed into Antarctica's extreme temperatures.

As the infographic shows, no single element is responsible. It's the unique combination of geography and planetary mechanics that locks the cold in place. These principles don't just dictate the continent's climate; they also explain its status as the world's largest polar desert. You can learn more about this apparent contradiction in our guide exploring if Antarctica is a desert and the surprising truth behind the ice.

A Foundation of Science for Expedition Readiness

Grasping these concepts is essential for anyone aspiring to travel to the high southern latitudes. Knowing why it's so cold allows you to anticipate challenges and prepare far more effectively. For instance:

- High Altitude: Directly impacts your physical performance and how efficiently your stove works. The air is thinner and holds much less heat.

- Earth's Orbit: Creates the six-month polar night, a period of intense, sustained cold with zero solar energy coming in. This presents profound mental and logistical challenges.

- The Ice Sheet: The albedo effect (its reflectivity) means most solar energy is bounced straight back into space, preventing any significant warming even during the 24-hour daylight of summer.

- Isolation: The Antarctic Circumpolar Current acts as a massive thermal barrier, stopping warmer ocean waters from ever reaching the continent.

At Pole to Pole, our philosophy is not to fight nature but to live within it. That begins with a deep, practical respect for the forces that shape these environments. Understanding the 'why' behind the cold is the first layer of your defence.

This scientific underpinning informs every aspect of our preparation, from the skills we teach at the Pole to Pole Academy to the specific kit we recommend for a Last Degree expedition. It is the bedrock upon which all successful polar journeys are built.

Why Altitude and Ice Form a Foundation of Cold

Antarctica’s profound cold starts with two simple but powerful facts: it’s the highest continent on Earth, and it’s almost entirely covered by a colossal sheet of ice. This is the fundamental difference between the poles. The Arctic is mostly frozen ocean sitting at sea level, but Antarctica is a solid landmass, a true continent. That single distinction is one of the biggest reasons it’s so much colder than its northern counterpart.

Think of the continent's interior as a permanent, high-altitude plateau. Just like mountaineers feel the temperature drop the higher they climb, Antarctica exists in a constant state of cold, thin air. For an expeditioner, this is not just an interesting fact; it dictates everything—oxygen levels, how well your stove functions, and the sheer, biting intensity of the cold you need to prepare for.

The Impact of Elevation

The South Pole itself sits at an elevation of roughly 2,835 metres (9,301 ft) . Before you even consider wind, darkness, or any other factor, this altitude guarantees a brutally cold baseline. The air up there is less dense, meaning it simply cannot hold heat the way air at sea level does. It’s a phenomenon you can feel on any high mountain, but here, it’s the norm.

This is fundamentally about air pressure. As you go higher, pressure drops, allowing the air to expand and cool. So, the continent’s extraordinary height is directly responsible for creating one of the most hostile environments on the planet. You can learn more about the key factors behind Antarctica's climate on discoveringantarctica.org.uk.

For anyone on the ice, this constant high-altitude exposure has very real, very practical consequences.

- Physiological Strain: Your body has to work much harder to pull the oxygen it needs from the thin air, which leads to greater fatigue. Acclimatisation is not just for Everest; it's a critical part of operating safely on the Antarctic plateau.

- Equipment Performance: Stoves burn less efficiently in a low-oxygen environment. This means that melting snow for drinking water—a vital daily chore—takes longer and burns through more precious fuel. That’s a calculation that has to be built into the logistics of every single trip.

- Temperature Intensity: The baseline temperature is already punishingly low because of the altitude alone. Add in other factors like wind or polar darkness, and the effective temperature plummets to levels that demand absolute respect and meticulous gear preparation.

The Ice Sheet: An Amplifier of Cold

Layered on top of the continent's high rock foundation is the Antarctic Ice Sheet. This is not a thin veneer; it's a monstrous reservoir of frozen water smothering 98% of the continent . In some places, this ice is over 4.5 kilometres (nearly 3 miles) thick .

This immense body of ice essentially doubles down on the altitude problem. It physically pushes the surface even higher into the colder layers of the atmosphere, amplifying the baseline cold already established by the landmass beneath. The ice acts as a massive, elevated platform, ensuring the surface temperature stays locked in a permanent deep freeze.

The Antarctic Ice Sheet does not just sit on the continent; it is the continent's surface. Its sheer mass and elevation are the first layers in a complex system that makes this the coldest place on the planet. Understanding this is the first step in preparing to face it.

For an explorer planning a Last Degree ski, this means the entire journey towards the pole is an ascent. You are not just crossing a flat, white desert; you are skiing steadily uphill towards a point nearly three kilometres above sea level. This slow, relentless gain in elevation is a constant physical and environmental challenge that shapes every single day on the ice.

The Rhythm of Darkness and Light: Earth's Tilt

It’s not just the altitude and the ice that make Antarctica so punishingly cold. A huge part of the story is written in the stars – or more accurately, in the way our planet moves through space. The entire rhythm of life and work on the continent is dictated by a simple astronomical fact: the Earth is tilted.

Our planet does not spin upright. It leans over by about 23.5 degrees . This slight tilt might seem insignificant, but for Antarctica, its consequences are profound.

The Long Polar Night

For six months of the year, that tilt means the South Pole is angled completely away from the sun. This is the austral winter, a period that plunges the entire continent into the long polar night.

From roughly March to September, the sun simply does not rise. Imagine months of 24-hour darkness. With no incoming solar energy to provide warmth, Antarctica continuously radiates what little heat it has left straight out into space. The temperature plummets to its absolute lowest.

The Weakness of the Midnight Sun

You’d think, then, that the summer would bring scorching relief. For six months, the continent is bathed in 24-hour daylight. But the ‘midnight sun’ offers surprisingly little warmth.

Because of that same planetary tilt, the sun never climbs high overhead like it does in the tropics. Instead, it hangs low, circling the horizon endlessly. This low angle is a double-edged sword, and both edges cut away at its heating power.

- A Thicker Atmosphere: The sun’s rays have to travel through a much deeper slice of the atmosphere to reach the ground. More of their energy gets scattered or absorbed before it ever has a chance to warm the ice.

- Spreading the Energy Thin: Think of shining a torch straight down on a surface—you get an intense, concentrated circle of light. Now, angle that torch. The beam spreads out, becoming weaker and more diffuse. The low-angle Antarctic sun does the same thing, spreading its energy over a massive area.

The result? You can be standing in brilliant, non-stop sunshine, yet the air temperature can remain dangerously cold. It’s a fundamental lesson for anyone heading south.

This cosmic cycle presents a dual challenge. You have to be ready for the profound mental and physical test of working in constant darkness, but also for the strange, unending light of a sun that offers no real heat.

The Expeditioner's Clock

This is not just a scientific fact; it's the unchangeable clock that every single polar operation runs on.

The expedition season is squeezed into a tiny window during the austral summer, usually from November to January. It’s the only time there’s enough light and the temperatures are just marginally less brutal. A Last Degree ski expedition, for instance, is timed to hit the peak of this summer period. Skiers push for eight to ten hours a day, covering 15-20 kilometres under a sun that never, ever sets.

This reality shapes every decision. High-quality glacier glasses are non-negotiable to fight the relentless glare bouncing off the snow. Tent discipline is key to forcing a sleep cycle when the sky gives you no cues.

Understanding this solar rhythm is as vital as knowing how to use your compass or layer your clothes. It’s the one constant you cannot change, so everything else has to adapt to it.

The Albedo Effect: A Planetary Refrigerator

Beyond its high altitude and lonely orbit, one of the most powerful forces keeping Antarctica locked in a deep freeze comes down to a simple matter of colour. The continent’s vast, white ice sheet acts like a gigantic planetary mirror, driving a phenomenon known as the albedo effect . It's a critical piece of the puzzle.

Simply put, albedo is a measure of how much solar energy a surface reflects. Dark surfaces, like tarmac or the open ocean, have a low albedo; they soak up the sun's energy and convert it into heat. A bright, white surface does the opposite, bouncing that energy straight back into space before it can be absorbed.

Fresh, clean snow is one of the most reflective natural substances on Earth. It can send up to 90% of incoming solar radiation right back where it came from. When you stand on the Antarctic plateau, you are standing on the largest single mirror on the planet.

A Powerful Feedback Loop

This incredible reflectivity creates a powerful, self-reinforcing cycle. Because the continent is already cold enough to be covered in ice and snow, it reflects away the very energy that could warm it. This ensures it stays cold enough to keep that ice and snow cover.

It’s a feedback loop that works like this:

- Initial Cold: Antarctica’s position and altitude make it cold.

- Ice Formation: The cold allows a massive ice sheet to form and persist.

- High Albedo: The white ice reflects most solar energy back into space.

- Reduced Warming: With little solar energy absorbed, the continent stays frigid.

- Loop Reinforces: The deep cold maintains the ice sheet, which continues to reflect heat, and the cycle repeats.

This is why even during the 24-hour daylight of the austral summer, the continent never truly thaws. The sun may be up, but its energy is being efficiently ejected back into the cosmos by the brilliant ice sheet below.

The albedo effect transforms Antarctica from merely a cold place into a highly efficient planetary refrigerator. The ice does not just exist because it is cold; the continent stays cold because the ice exists.

Practical Implications for Polar Travellers

For anyone travelling on the ice, this is not just a remote scientific concept; it has immediate, tangible consequences that dictate your equipment and daily safety drills. The sheer intensity of the reflected sunlight is a constant environmental hazard.

This reflected glare is why high-quality glacier glasses are not a luxury but an absolute necessity. Without proper eye protection, the immense amount of ultraviolet radiation bouncing up from the snow can quickly cause photokeratitis, or snow blindness. It’s a brutally painful condition that feels like having sand poured into your eyes and can cause temporary vision loss—a serious situation when you are days from any support.

Experienced explorers like Ranulph Fiennes and Børge Ousland understood this intimately. Their choice of eyewear was as critical to their survival as their choice of boots or stove. On our own training programmes in Svalbard, one of the very first lessons we instil is the non-negotiable discipline of protecting your eyes.

The table below starkly illustrates just how different polar ice is from other common surfaces, highlighting why Antarctica is so effective at staying cold.

Albedo Effect: A Comparison of Surfaces

| Surface Type | Solar Radiation Reflected (Albedo) | Implication for Temperature |

|---|---|---|

| Fresh Antarctic Snow | 80-90% | Massive cooling effect; very little energy is absorbed as heat. |

| Old Melting Snow | 40-60% | Moderate reflection; absorbs more heat as the surface darkens. |

| Bare Tundra/Rock | 10-20% | High absorption; surfaces heat up significantly in direct sunlight. |

| Open Ocean Water | <10% | Massive heat absorption; acts as a huge solar energy sink. |

This comparison shows exactly why the loss of sea ice in the Arctic is so concerning. As dark ocean replaces white ice, the region's albedo plummets, and it begins to absorb far more heat, accelerating warming. In Antarctica, the vast continental ice sheet maintains its high albedo—for now—locking the deep cold firmly in place.

How Wind and Water Keep Antarctica Isolated

The intense cold born on Antarctica’s high, reflective ice cap is fiercely guarded. Two of the most powerful natural barriers on the planet—the Antarctic Circumpolar Current and the polar vortex—work in tandem to build a fortress of cold, cutting the continent off from the world’s warmer weather.

For anyone planning a voyage south, these are not just abstract concepts. They are the very forces that forge the infamous volatility of the Drake Passage.

This isolation is a huge part of why Antarctica is so cold. Unlike the Arctic, where surrounding continents break up the ocean currents, the Southern Ocean is unique. With no landmasses to get in the way, a colossal current can race endlessly around the bottom of the world.

The Thermal Moat of the Southern Ocean

The Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC) is the largest ocean current on Earth. Flowing from west to east, it carries more than 100 times the flow of all the world's rivers combined . Think of it as a relentless, churning barrier of frigid water—a thermal moat protecting the continent.

This powerful current physically blocks warmer ocean waters from the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans from reaching Antarctica’s shores. It creates a sharp temperature boundary, keeping the cold locked in and deflecting warmer northern waters away.

Anyone who has crossed from South America has felt its power. The turbulent seas of the Drake Passage are a direct, visceral consequence of the ACC being squeezed through a relatively narrow channel. This experience is a key part of the journey from the gateway to Antarctica, Punta Arenas , preparing you mentally for the raw forces ahead.

The Polar Vortex: A Dome of Cold Air

Just as the ocean isolates Antarctica from below, the atmosphere walls it off from above. High in the stratosphere, a persistent, large-scale cyclone of powerful winds known as the polar vortex whips around the pole throughout the austral winter.

This vortex acts like a giant spinning container, trapping an enormous dome of intensely cold, dense, and dry air directly over the ice sheet. This containment stops the frigid polar air from mixing with warmer air from further north, reinforcing the continent’s deep freeze for months on end. The vortex is strongest during the long polar night when there is no solar energy to disrupt it, leading to the record-low temperatures recorded in the interior.

These two systems—the oceanic current and the atmospheric vortex—are not separate phenomena. They are two parts of a single, integrated system that creates Antarctica's profound isolation. The ocean keeps warm water out, and the sky keeps cold air in.

From an expedition standpoint, the practical results of this isolation are twofold:

- Volatile Access: The journey towards the continent, especially across the Drake Passage, is notoriously rough precisely because of the unimpeded power of these systems. Robust ships and solid preparation are non-negotiable.

- Stable but Extreme Cold: Once on the continent, this isolation leads to a more stable, albeit extremely cold and dry, climate. The weather is less subject to the fluctuating fronts you see elsewhere, but the baseline conditions are far more severe.

Understanding these isolating forces is key. They don’t just explain the continent’s climate; they explain the immense logistical and mental challenge of simply getting there. They are the guardians of Antarctica’s cold.

Putting The Science To Work On The Ice

Knowing why Antarctica is so brutally cold is one thing. Living and working within that reality is something else entirely. Out on the ice, the science is not theoretical—it’s the unforgiving force that dictates every single choice you make, from your grand strategy right down to the smallest daily routine.

Your layering system, for instance, is not just about putting on warm clothes. It’s your personal defence against the physics of high altitude and the relentless polar vortex. The methodical tent routines we drill into our teams are designed for one reason: to keep you functional when your fingers are numb and simple tasks feel monumental.

Of course, understanding the science is just the start. Heading into this environment without the right essential winter survival gear is simply not an option.

From Theory To Practice

Take something as basic as drinking water. The daily chore of melting snow becomes a constant fight against the continent's crippling dryness and sub-zero temperatures. It’s why meticulous preparation, like that of Roald Amundsen training on the Hardangervidda plateau, is not just a good idea—it’s the baseline for survival.

Every piece of kit becomes a critical tool. Your Hilleberg tent is not just shelter; it’s a life-support system when a blizzard hits. The performance of your stove at 2,800 metres is what stands between you and dehydration. This is why our entire philosophy is built on establishing competence long before you feel confident. Small mistakes here have huge consequences.

On top of this, you have to remember the continent itself is changing. Between 1950 and 2000, the Antarctic Peninsula warmed by about 3.2°C , which is more than three times the global average. For us, that means blending classic polar skills with the ability to navigate a more dynamic and unpredictable environment.

You do not fight nature in these environments—you learn to live within it. That means having a deep, practical respect for the forces at play, from katabatic winds that can scour a landscape bare to the deceptive power of a low-angled sun. Competence is your primary defence.

The Gear That Makes It Possible

This is where science directly shapes your packing list. That pulk you're hauling, weighing between 45-50kg , is filled with gear specifically chosen to function when the temperature plummets below -35°C . Every item has to justify its place, because both weight and reliability are everything.

Our approach to equipment is methodical and built on decades of hard-won experience. You can see exactly how these environmental factors translate into a real-world packing list by reading our detailed guide on how much kit it takes to face the coldest place on Earth.

Ultimately, understanding the science behind the cold is what allows you to move from being a mere visitor to becoming a capable, self-sufficient operator in the most demanding environment on the planet.

Unpacking Antarctic Weather: Your Questions Answered

If you are planning an expedition, Antarctica's climate is probably the biggest question mark. It's not just cold; it's a completely different kind of cold. Let's break down the common questions we get, so you understand what you’re up against.

Is Antarctica Really That Much Colder Than the Arctic?

Yes, and by a huge margin. The Arctic's average annual temperature sits around -18°C , which is hostile enough. But Antarctica? It averages a staggering -49°C .

This is not a fluke. The continent's high altitude, its sheer landmass, and the isolating effect of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current all work together to lock in the cold in a way the Arctic Ocean simply cannot.

What's the Coldest It Has Ever Gotten Down There?

The official record is mind-numbing. On 21 July 1983, scientists at Vostok Station recorded the lowest natural temperature on Earth: -89.2°C (-128.6°F) . This perfect storm of cold happened during the polar night under calm, clear skies, allowing every last bit of heat to radiate away into space.

So, Why Does the Extreme Cold Never Seem to Break?

It’s all about the polar vortex. Think of it as a ferocious, high-speed ring of wind circling the continent. This atmospheric fence is incredibly effective, trapping a massive dome of frigid air over Antarctica and blocking any warmer, mid-latitude weather from getting in. This creates a stable but brutally cold environment that persists for months on end.

Antarctica’s isolation by wind and sea makes it the planet’s most effective natural refrigerator.

What This Means for You and Your Gear

Understanding the why behind the cold is crucial for your preparation. This is not just about packing an extra layer; it's about survival.

- Timing Your Trip: There is a reason expeditions run from November to January. It is the Antarctic summer, offering continuous daylight and the "least extreme" temperatures. Any other time of year is a different game entirely.

- Your Kit is Your Lifeline: Every piece of gear needs to be up to the task. We are talking stoves that function flawlessly at altitude and in deep cold, multi-layered clothing systems, and navigation tools that will not fail you. A sudden cold snap is always a possibility, so your equipment must be rated to at least -40°C (-40°F) .

Getting your head around these conditions is the first step. Preparing for them is what will get you to your goal and back safely.

Ready to test your preparedness against the coldest place on Earth? Explore Pole to Pole expeditions and see what it takes to journey to the end of the world.