Is Antarctica a Desert? The Surprising Truth Behind the Ice

So, is Antarctica a desert? The answer is an unequivocal yes . In fact, it's the largest, driest, and coldest desert on the planet—a reality that often catches people by surprise. It forces you to throw out the mental image of sun-scorched sand and look at what really defines a desert.

The Coldest Continent Is Also Earth's Largest Desert

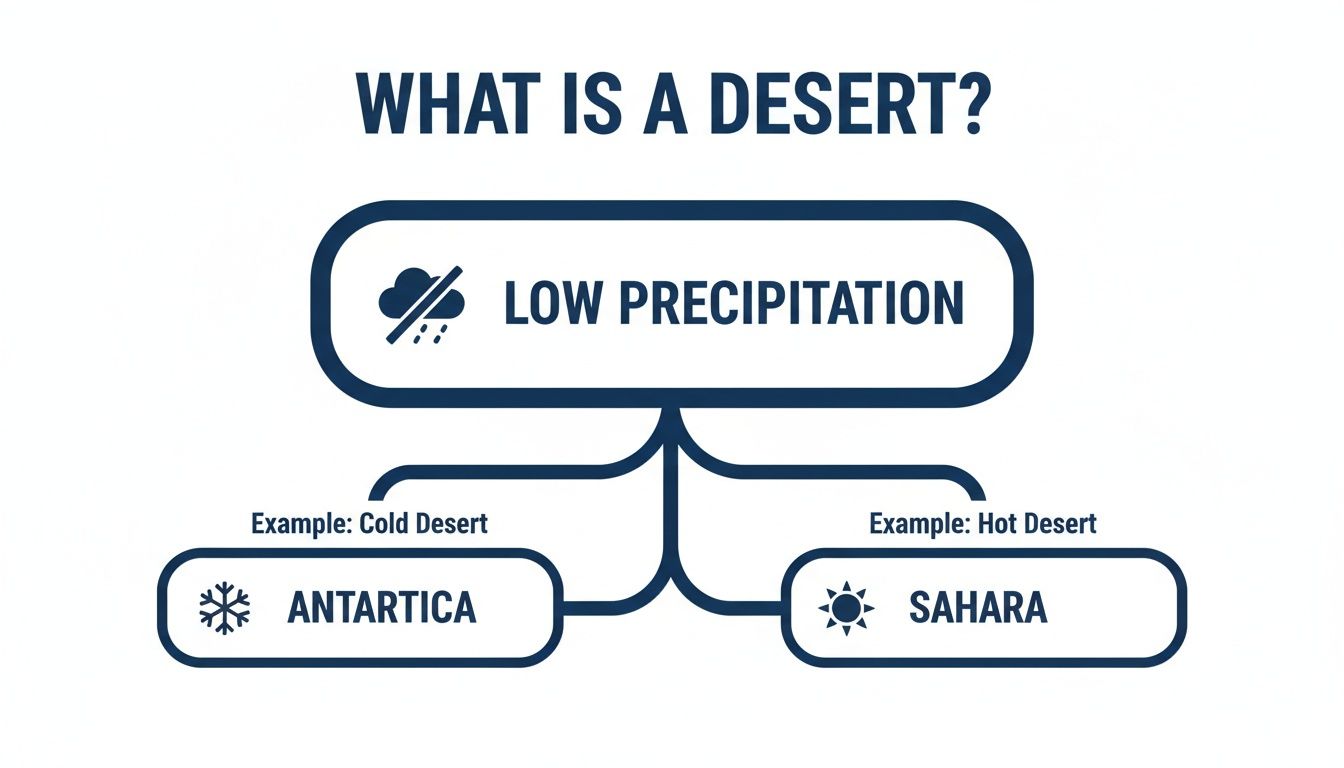

When you're planning an expedition, you learn to discard assumptions quickly. You have to focus on what actually defines the environment you're heading into. The single scientific factor that classifies a desert isn't temperature; it's the lack of precipitation.

A region is technically a desert if it receives, on average, less than 250 millimetres of precipitation per year.

Antarctica doesn’t just meet this criterion; it shatters it. The continent's extreme cold creates what's known as a polar high-pressure system—a huge mass of descending, bone-dry air that effectively blocks moisture from ever reaching the interior. The result is a vast polar plateau that gets almost no new snow.

A Land of Extremes

You don't have to take our word for it. UK scientists at the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) have been meticulously documenting these conditions for decades. Their research shows the high plateaux, often sitting above 4,000 metres (approx. 13,123 feet ), receive an average of just 50-200 mm of water equivalent each year. This profound dryness shapes every single aspect of how you travel, from your hydration strategy to the gear you trust with your life.

To give this some real-world context, here’s a quick comparison of the world's two largest deserts. It highlights how a lack of moisture, not heat, is the defining factor.

Defining a Desert: Antarctica vs The Sahara

| Characteristic | Antarctica (Polar Desert) | The Sahara (Hot Desert) |

|---|---|---|

| Average Precipitation | Less than 200 mm annually | Less than 100 mm annually |

| Defining Climate Feature | Intense cold, high pressure | Intense heat, high pressure |

| Primary Form of Precipitation | Snow and ice crystals | Rain (infrequent, intense bursts) |

| Size (approx.) | 14.2 million sq km | 9.2 million sq km |

| Key Environmental Challenge | Extreme cold and wind chill | Extreme heat and dehydration |

It becomes obvious that whilst they are worlds apart in temperature, both Antarctica and the Sahara are fundamentally defined by their aridity.

This dryness is one of the most critical factors for any team operating on the ice. It means the air actively sucks moisture from your body with every breath, making disciplined hydration a matter of survival, not just comfort. It's a key reason why our training at the Pole to Pole Academy places such a heavy emphasis on methodical stove operation and water-melting protocols. These aren't just camp chores; they're the essential skills for operating in the world's greatest desert.

Understanding the Mechanics of a Polar Desert

To really get your head around why Antarctica is a desert, you need to understand the powerful atmospheric forces that keep it so incredibly dry. This isn't just theory; for anyone planning a ski crossing, knowing these mechanics explains the stable but brutal conditions that shape every single decision you make out on the ice.

It all starts with the polar high-pressure system . Think of it as a colossal, invisible weight of cold, dense air constantly pressing down on the continent. This high pressure acts like a giant shield, blocking warmer, moisture-filled weather systems from ever reaching the interior. The air that does manage to sink from above is bone dry, having already dropped any moisture it might have held.

This system creates an environment that is fundamentally hostile to any kind of precipitation. It’s why the Antarctic Plateau is one of the most stable weather regions on Earth, but also one of the driest.

Katabatic Winds: The Scouring Force

Adding to this profound dryness are the relentless katabatic winds . These aren’t typical storm winds. They’re gravity-driven torrents of air. Cold, dense air from the high central plateau, which sits at over 2,800 metres (approx. 9,200 feet ), simply slides downhill under its own weight, gathering immense speed as it hurtles towards the coast.

These winds can blast at over 160 kilometres per hour (approx. 100 mph ), acting like a continental-scale scouring pad. They strip away any loose snow and suck any lingering moisture off the surface, turning it directly from solid ice into vapour—a process called sublimation—and carrying it away. For us on the ground, this means a constant, energy-sapping force you have to lean into for hours on end, and an environment where managing the moisture in your Fjällräven layering system becomes a matter of survival.

The infographic below shows how low precipitation is the one true definition of a desert, whether it's formed by intense cold or blistering heat.

As the image shows, the defining factor for both the Sahara and Antarctica is the tiny amount of precipitation they receive. It’s that simple.

This one-two punch of descending dry air and scouring winds creates an extreme precipitation shadow over the continent's interior. It’s an elegant but brutal system of atmospheric physics.

UK research puts hard numbers on Antarctica's desert status. Inland stations, like those run by the British Antarctic Survey, record less than 166 mm of precipitation a year. The data shows how the interior's high altitude and constant katabatic winds mean only a few centimetres of snow fall annually. This is equivalent to just 50 mm of water, cementing its status as a true cold desert. You can dig into the numbers yourself in the UK Science in Antarctica 2014-2020 report.

Navigating Antarctica’s Two Distinct Climates

To get to grips with Antarctica, you have to throw out the idea that it’s just one massive, uniform block of ice. It’s a common mistake. The reality is the continent is split into two very different regions, each with its own climate and its own set of challenges for any expedition.

Knowing the difference between the coast and the deep interior is fundamental. This is the kind of nuanced understanding that underpins every single Pole to Pole programme, because your life can depend on it.

The Antarctic Peninsula

First up is the Antarctic Peninsula, the finger of land that points up towards South America. In expedition circles, it’s sometimes wryly called the ‘banana belt’ of the continent. It’s a tongue-in-cheek name, of course, but it’s by far the mildest and wettest part of Antarctica, and where almost all tourist cruises end up.

Its maritime climate means warmer air and much more precipitation than anywhere else. This is also where the impacts of climate change are most visible, meaning anyone travelling here has to deal with dynamic conditions like shifting sea ice and fiercely unpredictable coastal weather. It’s the staging post for many deeper journeys, and getting to know its unique character is the first step south. For more on this, you can read about the gateway to Antarctica, Punta Arenas , the key logistical hub for polar teams.

The Interior Polar Plateau

In complete contrast, the interior is the real business—a true polar desert. This is the Antarctica of expedition folklore. A vast, high-altitude plateau that is profoundly cold, bone-dry, and hostile to all but the most meticulously prepared. Temperatures here can plummet below -80°C (-112°F), and the air is so dry it feels like it’s actively pulling moisture from your body.

The sheer scale of its aridity is staggering. Across its 14 million square kilometres , the interior highlands can see summer temperatures struggling to get above -50°C (-58°F), with less than 50 mm of water equivalent in annual snowfall. This is why training grounds like Svalbard, whilst excellent, can never fully replicate the brutal dryness and sheer scale of the continent’s deep interior. You can discover more insights about Antarctica’s regional climate variation on discoveringantarctica.org.uk .

For a polar explorer, this distinction is everything. The skills and equipment needed for a coastal journey are fundamentally different from those required to cross the desolate, arid heart of the continent.

Practical Skills for Surviving the Driest Place on Earth

Knowing Antarctica is a desert is one thing. Understanding what that means for your survival is something else entirely. This is where theory gets real, fast. The extreme aridity throws up unique challenges that demand methodical, disciplined routines. Simple camp tasks become critical survival procedures.

This isn’t about battling the environment. At Pole to Pole, we teach a different approach: understand the systems at play and move through them with competence. In a polar desert, this begins and ends with two things: water and warmth.

Managing Moisture Inside and Out

The first challenge is hydration. In the bone-dry air of the interior, you lose a huge amount of water just by breathing. Your only source is the snow beneath your skis, which means melting water is your absolute lifeline. It's a slow, fuel-hungry process that dictates your entire daily schedule.

The second, more subtle threat is managing the moisture your own body creates. Sweat is the enemy. Get your inner layers damp during a hard ski and then stop, and that moisture will freeze catastrophically close to your skin.

This principle is non-negotiable in a polar desert: staying dry is staying alive . Every decision, from how you vent your jacket to the pace you set, is governed by meticulous moisture management.

A precise layering system is everything. It's a constant dance of adjustment—adding or removing layers to stay comfortably cool, never warm enough to sweat. This is why we rely on proven kit, like high-performance base layers designed for one job: wicking moisture away from the body before it can cause a problem.

The Right Kit for the Job

Your equipment has to be utterly reliable. A failed stove isn't just an inconvenience; it's a life-threatening emergency. No stove means no water, no food, and a rapid spiral into hypothermia. This is why we depend on gear that has been proven over decades in the harshest conditions on Earth.

Getting your kit right is the foundation of any polar expedition. Each item has a specific role in managing the unique combination of extreme cold and aridity.

Essential Kit for a Polar Desert Crossing

| Equipment Category | Specific Item Example | Primary Function in Arid Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Stove System | MSR XGK-EX Stove | The expedition's engine room. Melts snow for drinking water and rehydrating food—your only source of hydration. |

| Shelter | Hilleberg Keron 4 GT Tent | Creates a crucial barrier against katabatic winds and provides a controlled space to manage moisture away from sleeping areas. |

| Sleep System | Layered Down & Synthetic Bags | Protects from ground cold whilst allowing body moisture to escape, preventing the bag from freezing solid from the inside out. |

| Clothing System | Technical Layering Apparel | Actively manages sweat by wicking it away from the skin, preventing the catastrophic 'flash freezing' when you stop moving. |

| Hydration | Wide-Mouth Insulated Flasks | Prevents your freshly melted water from re-freezing during the day, ensuring you can stay hydrated whilst on the move. |

This isn't just a packing list; it's a system where every component works together to keep you alive.

Mastering these skills is not just about comfort; it's about building the competence that creates true confidence in an unforgiving environment. To develop these skills further, it's worth consulting a dedicated guide on A Practical Guide to Camping in Snow and Staying Warm.

For a much deeper look into our specific equipment choices and the thinking behind them, see our complete guide on how much kit it takes to face the coldest place on earth .

Building the Mindset for a World of Ice and Sky

Beyond the physical work, a polar journey is a game played almost entirely in the mind. The first step to winning that game is understanding that Antarctica is a desert—a vast, dangerously arid landscape that couldn't care less about you. It completely reframes the challenge. You stop thinking about conquering an obstacle and start thinking about how to move competently through a powerful, unique ecosystem.

An expeditionary mindset is built on this foundation of respect. It has a lot in common with military discipline: the methodical routines, the unwavering focus on the process, and the ability to hold it together when you’re totally isolated with a small team. Your entire world shrinks to the task right in front of you, whether that’s navigating a total whiteout or just getting a stove lit at -35°C .

The Psychology of the Long Haul

Maintaining focus during those monotonous eight-hour ski days, pulling a 50kg pulk over what feels like an endless sea of sastrugi, demands a very specific kind of mental toughness. It has little to do with fleeting motivation and everything to do with ingrained habit and a clear sense of purpose. You quickly learn the difference between determination and stubbornness—one gets you home, the other gets you into serious trouble.

This is the exact mindset that defined the great polar explorers. Roald Amundsen’s success wasn't down to brute force; it came from meticulous preparation and a deep understanding of the environment he was walking into. He learned from the Inuit, respected the conditions, and planned every detail accordingly.

Success in a polar desert isn’t about fighting nature; it's about not having to. It’s the result of preparation so thorough that your actions become automatic, freeing your mind to make critical decisions when it really matters.

This deep psychological preparation is every bit as crucial as your physical training. In fact, your physical endurance is often a direct result of your mental state. Knowing why the air is so punishingly dry helps you commit to the relentless, soul-destroying task of melting snow for water. Understanding why the landscape is so empty helps you find focus within it. It’s this mental conditioning that transforms a difficult experience into a purposeful journey. We explore this very concept in our guide on training for the unknown to prepare your mind and body , which is essential reading for anyone serious about this.

Ultimately, the answer to "is Antarctica a desert?" is more than just a piece of trivia. It's a framework. It shapes your preparation, dictates your actions on the ice, and helps you build the quiet authority needed to travel safely and respectfully through that silent world of ice and sky.

Protecting the World's Last Great Wilderness

Knowing Antarctica is a desert isn't just a quirky fact. It’s the key to understanding just how fragile the continent is.

Drop a wrapper or spill a bit of fuel in a temperate forest, and nature will eventually take care of it. But here, in a brutally cold and dry desert where the ice sheet barely moves, any mark we make stays put for an alarmingly long time.

That footprint—whether it's a single boot print in the snow or microbial contamination from a stray crumb—becomes locked into the ice, virtually unchanged. It’s a sobering thought, and it’s why our entire approach to exploration must be one of absolute stewardship.

Leave No Trace in a Polar Desert

The principle of ‘Leave No Trace’ isn't just a guideline here; it's an iron-clad rule. On a polar expedition, this commitment is absolute, enforced by the stringent biosecurity protocols of the Antarctic Treaty System that governs everything we do on the continent.

Every single item, right down to the last drop of wastewater, has to be contained, packed up, and removed. There are no shortcuts. No exceptions.

In the world’s driest, coldest desert, nothing disappears. Respect for the environment isn't an option; it's a fundamental requirement built into every aspect of expedition planning and execution.

Competence and Care

This ethos is at the heart of the Pole to Pole philosophy. We don’t see our expeditions as just personal endurance tests. We see them as acts of respectful, competent presence in a wilderness that is globally significant.

It's a responsibility we take very seriously. From the first day of training at the Academy, this mindset of meticulous care is drilled into everyone. Our teams learn that true expertise in this environment isn't measured by the distance you cover, but by the complete lack of any trace you leave behind.

Travelling through the Antarctic desert is a privilege. And that privilege comes with the duty to protect it for generations to come. This is the quiet authority that guides every single journey we lead.

A Few Lingering Questions

Even when you know the facts, the idea of a frozen desert can feel counterintuitive. Let's tackle a few of the questions that often come up when people start to grasp the reality of Antarctica.

If It’s a Desert, Where Did All the Ice Come From?

It’s a good question. The answer lies in time, not quantity. Antarctica’s immense ice sheet is the product of thousands upon thousands of years of snowfall.

Even though the annual snowfall is tiny, the temperatures are so brutally cold that it never gets a chance to melt. Over millennia, layer builds on layer, and the sheer weight of the accumulated snow compacts it into the dense glacial ice that now covers the continent, reaching up to 4.7 kilometres thick in places. It's an incredible lesson in how small, consistent inputs can build something colossal over geological time.

Which Is More Dangerous: a Hot Desert or a Cold Desert?

They're different worlds, and each demands its own brand of respect. Neither is 'more' dangerous; they're just dangerous in completely different from each other.

In a hot desert like the Sahara, your biggest enemies are heatstroke and dehydration from sweating out your body’s moisture. In the Antarctic polar desert, the threats are hypothermia, frostbite, and dehydration from the bone-dry air stealing moisture with every breath you take. One is about managing heat; the other is about managing cold. The skills are so specific that expertise in one environment doesn’t really prepare you for the other.

Does Anything Actually Live in the Antarctic Desert?

On the vast, inland plateau? Almost nothing. The interior is almost entirely microbial.

The wildlife everyone pictures—penguins, seals, seabirds—lives exclusively on the coastal fringes and the Antarctic Peninsula. These animals are completely dependent on the Southern Ocean for their food. The inland desert itself is one of the most sterile, lifeless landscapes on Earth, which only makes the creatures clinging to its edges seem that much more resilient.

At Pole to Pole , we believe that understanding an environment is the first step towards moving through it with competence and respect. Our training and expeditions are built on this foundation of genuine knowledge. To explore your possible, visit us at https://www.poletopole.com.