Animals in the North Pole: An Essential Arctic Wildlife Guide

Out here, the High North sets the rules. This is a living, breathing ecosystem, and we are temporary visitors passing through. When you’re in our expedition zones, such as the sea ice north of Svalbard, the main residents are the formidable polar bear, the resilient Arctic fox, and the seal populations they both depend on.

Learning about these animals is not a box-ticking exercise. It is a fundamental part of travelling safely and responsibly in their world.

Your Place in the Arctic Ecosystem

The first lesson the Arctic teaches is humility. We are guests in a wild domain that has thrived for millennia without any help from us. At Pole to Pole, our entire philosophy is built on teaching people to work with this environment, not against it. That mindset begins with a deep respect for its inhabitants.

This guide is not just about identifying animals. It is about building operational intelligence. Knowing how to read an animal's behaviour informs critical decisions on the ground, from where you pitch your tent to how you manage your daily routine. It’s about cultivating a constant state of awareness, a core principle we drill into every expeditioner at the Pole to Pole Academy in Iceland, located at 64° 25' 24" N.

Key Species in Expedition Zones

In places like Svalbard, where we run much of our training, you will find a tightly interconnected food web. The presence of one species almost always tells you something about another.

- Polar Bear ( Ursus maritimus ): The apex predator. Their entire world revolves around the movement of sea ice and where they can find seals.

- Seals (Ringed and Bearded): The absolute cornerstone of the polar bear's diet. If you see seals hauled out on the ice, you’re in polar bear country.

- Arctic Fox ( Vulpes lagopus ): A true master of survival. These curious, tough animals are often seen scavenging around the edges of expedition life.

- Cetaceans (Beluga, Narwhal): Spotting these 'ghosts of the Arctic' near the ice edge is a rare privilege, a profound reminder of the richness hidden beneath the ice.

- Walrus ( Odobenus rosmarus ): Huge, powerful, and surprisingly social. They command a wide berth and a huge amount of respect, whether on shore or ice.

- Seabirds (Kittiwakes, Guillemots): Their enormous seasonal colonies completely change the sound of the coast and point to nutrient-rich waters below.

We don't fight nature — we live in it. This is not just a saying for us; it’s central to our training. Understanding the animals of the North is the first step. Turning that knowledge into practical fieldcraft is what keeps you safe and makes the experience truly meaningful.

This guide is your foundation. It’s the essential knowledge you need to build competence before you can earn confidence. Use it to prepare for a safe, responsible, and unforgettable journey through one of the planet's last great wildernesses.

The Polar Bear and Expedition Safety Protocols

In the Arctic, the polar bear ( Ursus maritimus ) is the undisputed sovereign. Seeing one in the wild is a profound, unforgettable experience, but it’s one that demands absolute respect and serious preparation. For any expeditioner, understanding this animal is about more than just biology—it’s about operational safety and, ultimately, survival.

A polar bear is an animal engineered for efficiency. Its entire existence boils down to a simple equation: energy spent versus calories gained. This calculation drives its every move, making it exceptionally curious and relentlessly persistent. Every single person who enters its world must factor these traits into their planning and daily routines.

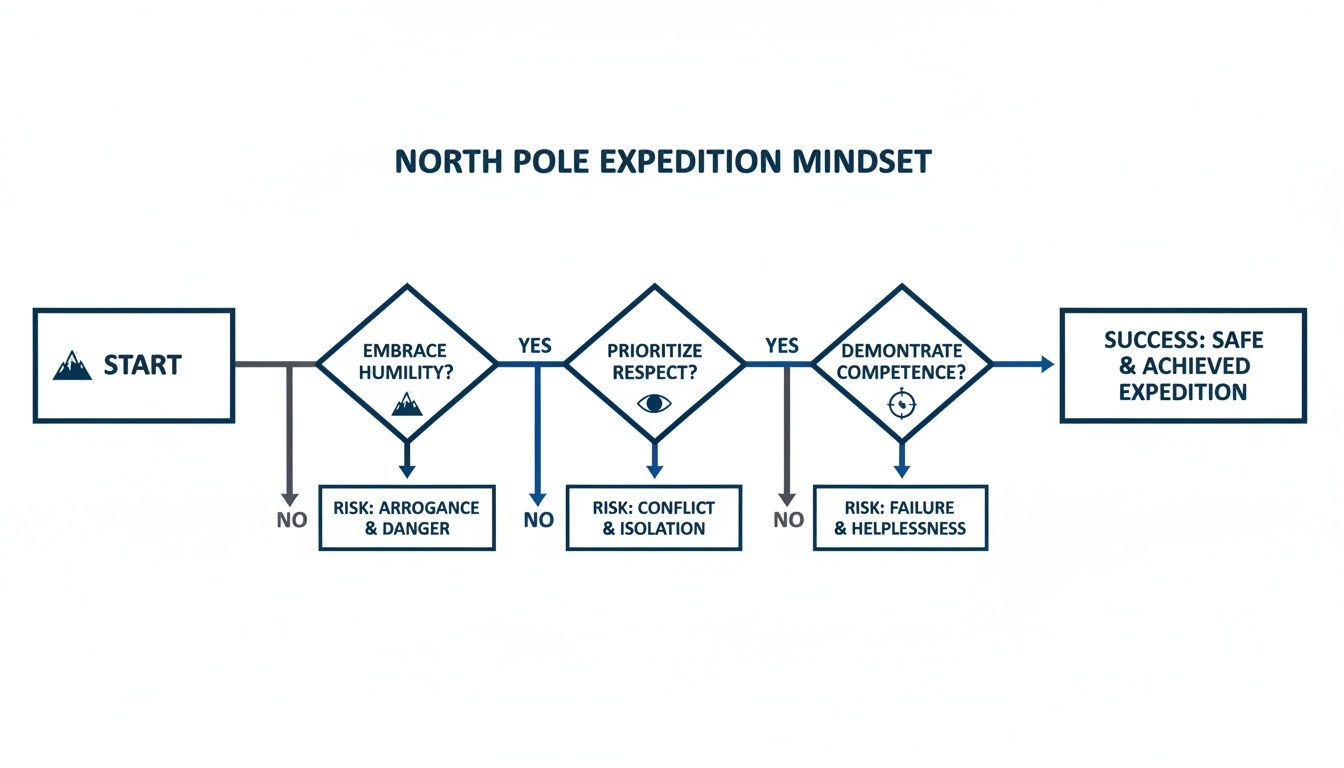

This flowchart maps out the core mindset for travelling safely in polar bear country. It’s a philosophy that starts with humility, builds into respect, and results in real-world competence.

This decision-tree approach is not just a process; it's a reminder that true field competence is built on a foundation of genuine respect for the environment and the animals that call it home.

Understanding Polar Bear Behaviour

The primary driver for a polar bear is the hunt for seals. This one fact dictates almost everything about where you might find them. They travel huge distances across the sea ice, using an incredible sense of smell to locate seal breathing holes or pupping lairs hidden under the snow.

Knowing that up to 80% of a polar bear's diet is seals is not just a statistic; it’s tactical information that shapes our entire route.

We operate with the constant awareness that if the landscape is good for seals, it’s prime polar bear territory. This means we avoid complex pressure ridges where a bear could approach unseen and stay hyper-vigilant when near open water leads in the ice. This is not a new idea. Back in 1773, a British Arctic Expedition led by Captain Constantine Phipps provided the first detailed scientific description of the polar bear—a legacy that still informs our modern safety protocols.

Fieldcraft and Camp Security

Our entire operational philosophy is built on one principle: avoidance over confrontation. The goal is to see a polar bear from a safe distance—if at all—and ensure it never learns to associate humans with a potential meal. We achieve this through meticulous fieldcraft and rigid camp security protocols, skills we drill into every team member on our expedition training course.

Our non-negotiable procedures are simple but effective:

- Deterrents: Every guide and team member carries appropriate deterrents. This can range from flare pistols to, where mandated by local law like in Svalbard, firearms. These are strictly last-resort tools, to be used only to protect human life.

- Tripwire Systems: We establish a perimeter fence with integrated flares or blank charges around every single camp. It’s an early warning system designed to scare off a curious bear long before it gets too close.

- Scent Discipline: All food, rubbish, and scented items are sealed in bear-proof containers stored well away from tents. We cook downwind and take extreme care to leave no trace of food behind.

- Polar Watch: A rota for a 24-hour watch is non-negotiable. There is always a vigilant team member on duty, scanning the horizon. This is a fundamental part of team safety.

The best polar bear encounter is one that does not happen. Our training is not about being prepared for a fight; it is about having the discipline and awareness to avoid one altogether. This is the difference between recklessness and professional expedition conduct.

Ultimately, safety in polar bear country is not about a single piece of equipment, whether it’s a Hilleberg tent or a specific rifle. It’s a system of behaviours. It's a mindset of constant vigilance, disciplined routine, and an unwavering respect for the true apex predator of the Arctic.

Seals as the Foundation of the Arctic Food Web

To really get to grips with the Arctic, you first have to understand its seals. They are the engine room of the High North. Their presence dictates where every major predator goes and acts as a direct measure of the marine ecosystem's health.

For an expeditioner, this is not just trivia; it's practical intelligence. Spotting a landscape dotted with the breathing holes of ringed seals tells you one thing immediately: you are in a prime polar bear hunting ground. That simple observation sharpens your situational awareness and changes how you think about camp placement and travel routes.

This link between seals and survival is nothing new. Think back to the Royal Navy's early polar ventures, like Captain David Buchan's 1818 push towards the Pole. For crews trapped in the ice, seals were a critical resource, providing an estimated 50% of dietary fats that helped keep scurvy at bay. Today, data from modern UK Arctic programmes estimates there are 1.5-2 million ringed seals ( Pusa hispida ) across the North Pole basin. They're a population that sustains up to 70% of polar bear diets in some areas. You can read more about these early naval expeditions and their reliance on local wildlife on jamesfitzjames.com.

Key Seal Species for North Pole Expeditioners

Whilst you’ll find several seal species in Arctic waters, there are a couple that are especially relevant for expedition teams because of their relationship with the very sea ice we travel on. A competent explorer knows the difference and what their presence means.

The table below is a quick field guide to the seals you're most likely to encounter, particularly in key expedition hubs like Svalbard.

Key Seal Species for North Pole Expeditioners

| Species | Key Identification Features | Typical Location | Relevance to Expeditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ringed Seal ( Pusa hispida ) | Smallest Arctic seal; dark spots with light rings. | Stable, snow-covered 'fast ice'. | The main food source for polar bears. Their breathing holes and birth lairs are magnets for hunting bears, especially in spring. |

| Bearded Seal ( Erignathus barbatus ) | Much larger; prominent, long whiskers; square fore-flippers. | Shallower waters, near moving or broken pack ice. | Their presence signals more dynamic ice conditions and often richer, shallower feeding grounds. Less of a direct link to hunting polar bears. |

Knowing which seal is which gives you a clearer intelligence picture of the environment you're moving through.

The presence of ringed seals means a higher probability of polar bears actively hunting for pups in the spring. Sighting bearded seals suggests dynamic ice conditions and potentially richer, shallower waters.

Practical Implications for Expedition Teams

This is where theory becomes practice. When you’re planning a day's travel, knowing that ringed seals need stable, snow-covered ice for their birth lairs helps you identify likely hunting grounds.

So, when skiing across a vast ice pan in Svalbard, a guide might steer the route away from terrain that looks perfect for seal lairs. It’s a simple decision that reduces the chance of a surprise encounter with a predator.

This is the essence of the Pole to Pole philosophy. We do not try to conquer nature; we learn to move through it with understanding. Every element, from the direction of the wind to the type of seal hauled out on the ice, is a piece of information. The ability to read these signs is what separates a tourist from a capable expeditioner. It's this deep environmental literacy that underpins safety and success amongst the animals of the North Pole.

The Arctic Fox: A Masterclass in Adaptation

If any animal truly lives the expedition mindset, it’s the Arctic fox ( Vulpes lagopus ). Small, tenacious, and perfectly engineered for its world, the fox is a lesson in survival. Watching one move through the landscape is to see energy conservation and situational awareness in its purest form—principles we drill into every participant at our Academy.

This creature is not just a fleeting glimpse of white against the snow. It is a highly specialised predator and an ingenious scavenger, absolutely vital to the North Pole's ecosystem. Its ability to not just endure, but to genuinely thrive, offers a powerful parallel to the skills needed for any successful expedition.

Engineered for the Cold

The Arctic fox's adaptations are a blueprint for surviving extreme cold. The most obvious is its coat, which shifts from a mottled brown or grey in summer to a thick, brilliant white in winter. This incredibly dense fur provides such superb insulation that the fox can maintain its core body temperature even when the air plummets to -50°C or below.

But it goes deeper than just the fur.

- Counter-current heat exchange: A clever circulatory system in its paws keeps its footpads just above freezing, preventing heat loss to the snow without risking frostbite.

- Compact form: Its short legs, muzzle, and rounded ears are all about minimising surface area. Less exposure means less body heat lost to the bitter air.

- Acute hearing: It can pinpoint the sound of lemmings tunnelling up to 12 centimetres (nearly 5 inches) under the snow—a critical skill for hunting in the dead of winter.

This is biological efficiency at its finest. Every single adaptation is designed to conserve precious calories, a mindset every polar traveller must adopt when managing their own energy reserves on a long, hard ski day.

Predator and Scavenger

The fox is a versatile hunter, but its fate is famously tied to the boom-and-bust cycles of lemmings. Drawing from a long history of British polar research, modern data shows that fox populations in the High Arctic can swing by as much as 40% biennially , directly linked to the availability of these rodents. In Svalbard, a key gateway for our North Pole trips, the population is estimated at around 1,200 foxes across its 61,000 km² expanse.

These numbers highlight a core truth of any expedition: adapt or fail. When lemmings are scarce, the fox does not give up; it changes its strategy entirely. It becomes a scavenger, shadowing polar bears to clean up the remains of seal kills or combing coastlines for seabird eggs and carrion.

This flexibility is a powerful reminder of the need for adaptable decision-making under pressure. The fox’s ability to survive temperatures of -70°C by digging dens 2-3 metres deep boosts its survival rate by 60% compared to staying on the surface—a clear parallel to how our winter survival training gives participants the edge. You can learn more about the legacy of UK-led polar research and its findings on MBA.ac.uk.

The Arctic fox does not complain about the conditions; it simply adapts its behaviour to meet them. This is the essence of the expedition mindset: focus on what you can control and adjust your plan accordingly.

Encountering Foxes Responsibly

Whilst often curious and seemingly bold, the Arctic fox is a wild animal and demands respect. In places like Svalbard, foxes can become used to humans, which is dangerous for them and for us.

Disciplined camp hygiene is non-negotiable. Storing all food in sealed containers and ensuring zero scraps are left behind is critical to avoid attracting them. A fox that learns to associate tents with an easy meal can become a real nuisance, chewing through expensive kit like Hilleberg tents or pulk covers.

More seriously, Arctic foxes can carry rabies. Any bite or even a scratch must be treated as a serious medical incident. Observe them from a distance, appreciate their incredible tenacity, and ensure your presence leaves no trace.

Life Beyond the Ice Edge: Marine Mammals and Seabirds

Whilst our focus on an expedition is often fixed on the immense sea ice, the Arctic reveals another world at its edges. Where ice meets open water, a different community of animals thrives, offering a much broader perspective on this incredibly complex place. Knowing what to look for here is not just for sightseeing; it's a vital part of navigation and appreciating the sheer richness of life that exists just beneath the surface.

This meeting point—the marginal ice zone—is a place of constant change and immense productivity. It's here you might catch a glimpse of the true phantoms of the Arctic Ocean.

The Ghosts of the Arctic Ocean

Sighting a Beluga or a Narwhal is a rare privilege. These whales are masters of a life dictated by pack ice, using their incredible sonar to navigate the dark, shifting waters beneath the frozen world you're travelling across.

-

Beluga Whales ( Delphinapterus leucas ): Often called the "canaries of the sea" for their incredible range of clicks, whistles, and calls, these brilliant white whales travel in tight-knit social pods. You're most likely to spot them in the summer months along the coasts of Svalbard, especially in fjords where river meltwater creates a feast.

-

Narwhals ( Monodon monoceros ): Famed for the male's single, spiralled tusk—actually an elongated tooth that can grow up to 3 metres long—the Narwhal is a much more elusive creature. Seeing one is a definitive sign you're in the High Arctic. They rarely stray from the dense pack ice, which offers them protection from predators like orcas.

A flash of white in the dark water is a powerful reminder of the vast, unseen world thriving just metres below your pulk.

The Power of the Walrus

Few animals command respect quite like the walrus ( Odobenus rosmarus ). These enormous pinnipeds can weigh over 1,500 kilograms and are a formidable presence, whether hauled out on an ice floe or cruising through the water. Their long tusks are not just for show; they're essential tools for hauling their immense bodies onto the ice and for defence.

Observing a walrus haul-out—a gathering that can number in the hundreds—is an incredible, noisy, smelly experience, but one that demands absolute caution. They are easily disturbed and can be aggressive if they feel threatened. Keeping a respectful distance of at least 150 metres is a non-negotiable rule. Their presence on a coastline dictates everything, from your approach route to where you can safely land.

The walrus is a perfect example of how expedition conduct must be dictated by the wildlife, not the other way around. Their space is their space, and our plans must adapt accordingly. This is a core principle of responsible polar travel.

Svalbard's Thundering Seabird Colonies

Come summer, the coastal cliffs of places like Svalbard completely transform. They become deafening, chaotic cities of birds. The air fills with the calls of tens of thousands of nesting seabirds—a spectacle that truly underscores the incredible seasonal pulse of Arctic life. You can learn more about seeing this for yourself in our definitive guide to Svalbard.

Vast colonies of Kittiwakes and Brünnich’s Guillemots cling to sheer rock faces. Their guano fertilises the sparse tundra below, creating impossible pockets of vibrant green against the grey rock. Their frantic activity is fuelled by the rich supply of fish and crustaceans just offshore.

For an expeditioner, these bird cliffs are more than just a sight to behold. They are living signposts, indicating nutrient-rich currents and a thriving marine food web. They help complete the picture of a polar environment that is complex, interconnected, and demands our constant awareness.

Responsible Conduct in a Fragile Environment

All our advice boils down to a simple, practical code of conduct. This is not about empty slogans; it’s about a deep, guiding principle of responsible exploration. True polar journeys are built on competence and respect, and that means specific, actionable guidelines for minimising your footprint on Arctic wildlife.

It’s about moving with purpose and awareness. Watching these animals requires a quiet discipline, ensuring our presence never changes their natural behaviour. If an animal moves, flees, or alters its feeding because of you, that’s a significant disturbance.

Field Rules of Engagement

To turn respect into tangible action, we operate under a few strict but simple rules. These are not negotiable. They are the protocols that protect the fragile world we’re so privileged to visit.

- Distance is Respect: Keep a minimum distance of 100 metres from larger mammals like polar bears and walruses. For smaller animals, your binoculars and long lens are your best friends. Do not close the gap.

- No Trace Discipline: Everything you bring in, you take out. That includes every last scrap of organic waste. A single stray crumb can attract scavengers like the Arctic fox, dangerously habituating them to us.

- Ethical Photography: Your photograph is never more important than an animal's wellbeing. Avoid flash, sudden movements, or using drones—they can cause extreme stress.

Beyond our direct wildlife encounters, embracing sustainable camping practices is fundamental to reducing our overall impact on these delicate lands.

In a place where survival is a daily fight for its inhabitants, our duty is to pass through without adding to their burden. Our presence should be fleeting, our impact negligible.

The Arctic is changing. Fast. Retreating sea ice directly threatens the hunting grounds of polar bears and the pupping lairs of seals. This is not a future problem; it's happening right now, which makes responsible travel more critical than ever.

Every single decision—from where we pitch a tent to how we manage waste—matters. Our approach reinforces the mindset that travelling here is a privilege, one that demands the highest standards of conduct. This philosophy is at the very heart of our training, which you can see in our practical guide to travelling in Greenland.

Your Questions Answered: Arctic Wildlife

We receive a lot of questions from people preparing for their first trip north. Here are straight answers to some of the most common ones, drawn from years of experience on the ice.

What's the Most Dangerous Animal in the Arctic?

Let's be direct: it is the polar bear ( Ursus maritimus ). No other animal in the Arctic actively views humans as prey. It is why they command our absolute respect and dictate every safety protocol we have.

But here’s the thing – the real danger is not the bear itself. It's complacency. With the right training, a disciplined team, and a constant focus on avoiding encounters in the first place, the risk becomes manageable.

How Close Can We Get?

Our guiding principle is simple: our presence should never change an animal's behaviour. We are there to observe, not to interact. We stick to strict, often legally required, minimum distances.

- Polar Bears & Walruses: We keep a minimum of 100-200 metres between us. That’s what binoculars and long camera lenses are for.

- Seals & Foxes: They might seem more relaxed, but we still keep our distance. The goal is to avoid causing stress or letting them get used to humans.

A good wildlife encounter is one where the animal either does not know you're there or simply does not care. That's the hallmark of a professional, responsible expedition.

Can I See Animals and the Northern Lights on the Same Trip?

It’s a great image, but it comes from a misunderstanding of how the Arctic seasons work. Seeing the Northern Lights requires darkness. Deep, winter darkness.

Our prime season for spotting wildlife out on the sea ice is during the spring and summer, when the sun never sets and we have 24-hour daylight . You simply cannot have both on the same expedition; they belong to two completely different times of the year.

What if I Run Into a Polar Bear?

Your immediate actions will depend entirely on the situation, which is exactly why the hands-on training at our Pole to Pole Academy is so critical.

That said, the core principles never change: Stay calm. Do not run. Keep your eyes on the bear and alert your guide immediately. Your guide is an expert in deterrent procedures and will take charge. Your only job is to follow their instructions, instantly and without question.

At Pole to Pole , we know that true competence is the bedrock of any great adventure. Our courses and expeditions are designed to give you the skills and the mindset to travel safely and responsibly through the world's most incredible environments. Explore your possible with us.