How hard is it to climb Mount Everest: a clear, practical guide

So, you want to know how hard it is to climb Mount Everest?

Let’s start by looking past the summit photographs and the victory smiles. The real story isn't about one heroic push to the top. It's about enduring a gruelling, two-month test of physical endurance, mental fortitude, and hard-earned technical skill —all in an environment that is brutally indifferent to human ambition. Success out here has little to do with a single day's strength and everything to do with methodical, long-term resilience.

Decoding the Everest Challenge

Climbing Everest is an immense undertaking, and it demands far more than just being in peak physical shape. The true difficulty is a tangled web of challenges, each one making the others worse over the long, slow grind of an expedition. Yes, modern logistics and incredible Sherpa support have opened the door for more people than in the pioneering days of Hillary and Tenzing, but they haven't made it easy. Not by a long shot.

The mountain's objective dangers—from the ever-shifting, creaking labyrinth of the Khumbu Icefall to the notoriously fickle weather—are a constant, serious threat. But often, the real battle is the one fought inside your own head.

The Mental and Physical War

At its core, an Everest expedition is a profound physiological and psychological test. Whether you succeed or fail often boils down to a few key things:

- Adaptation to Altitude: Your body's ability to acclimatise is non-negotiable. You’re trying to function in an atmosphere with only one-third of the oxygen you're used to at sea level.

- Sustained Performance: This isn't a weekend climb. It’s about being able to perform, day after day, for weeks on end. It’s about meticulously managing your energy through acclimatisation rotations and frustrating rest periods.

- Mental Resilience: Your mind has to endure it all. The crushing monotony of Base Camp, the waiting, the doubt. All of this is followed by the need for intense, high-stakes decision-making in the "Death Zone" above 8,000 metres .

Beyond the physical and environmental threats, the climb demands an immense amount of mental toughness for athletes , a skill that truly dictates how you perform when you are under the most extreme pressure imaginable. It is this raw combination of internal and external pressures that defines the Everest experience.

In our experience, determination without competence is dangerous. The goal is not to conquer the mountain but to develop the skills and judgement to move within its environment safely. This requires a shift in mindset from a singular focus on the summit to a deep respect for the entire process.

This guide will break down what the challenge really looks like. We'll move from the physiological war your body wages against altitude to the practical skills and mental grit required to stand on top of the world.

The Physiological War Against Altitude

Forget the rock and ice for a moment. The real battle on Everest is fought inside your own body.

Down here at sea level, the air is about 21% oxygen. By the time you reach Base Camp at 5,364 metres , that number is slashed in half. And on the summit? You're trying to perform the most demanding physical act of your life on less than a third of the oxygen your body was designed to run on.

This relentless oxygen starvation, known as hypoxia , is the engine behind Everest's difficulty. It degrades everything you do, physically and mentally. Imagine trying to run a marathon whilst breathing through a cocktail straw. That’s the kind of strain your heart and lungs are under, with every single step.

Life in the Death Zone

The name isn't for dramatic effect. The ‘Death Zone’—the air above 8,000 metres (26,247 feet) —is a very real physiological line in the sand. Up here, your body simply cannot acclimatise. No matter how fit or strong you are, it begins to shut down. You are, quite literally, on a timer.

Inside this zone, the lack of oxygen unravels you:

- Cognitive Decline: Simple decisions become exhausting. You can forget basic safety checks or misjudge a simple risk.

- Physical Impairment: Your coordination goes. Just clipping into a safety line can feel like threading a needle in the dark with frozen fingers.

- Increased Risk of Frostbite: Hypoxia cripples circulation, leaving your fingers and toes incredibly vulnerable to the brutal cold, where temperatures can drop to -35°C.

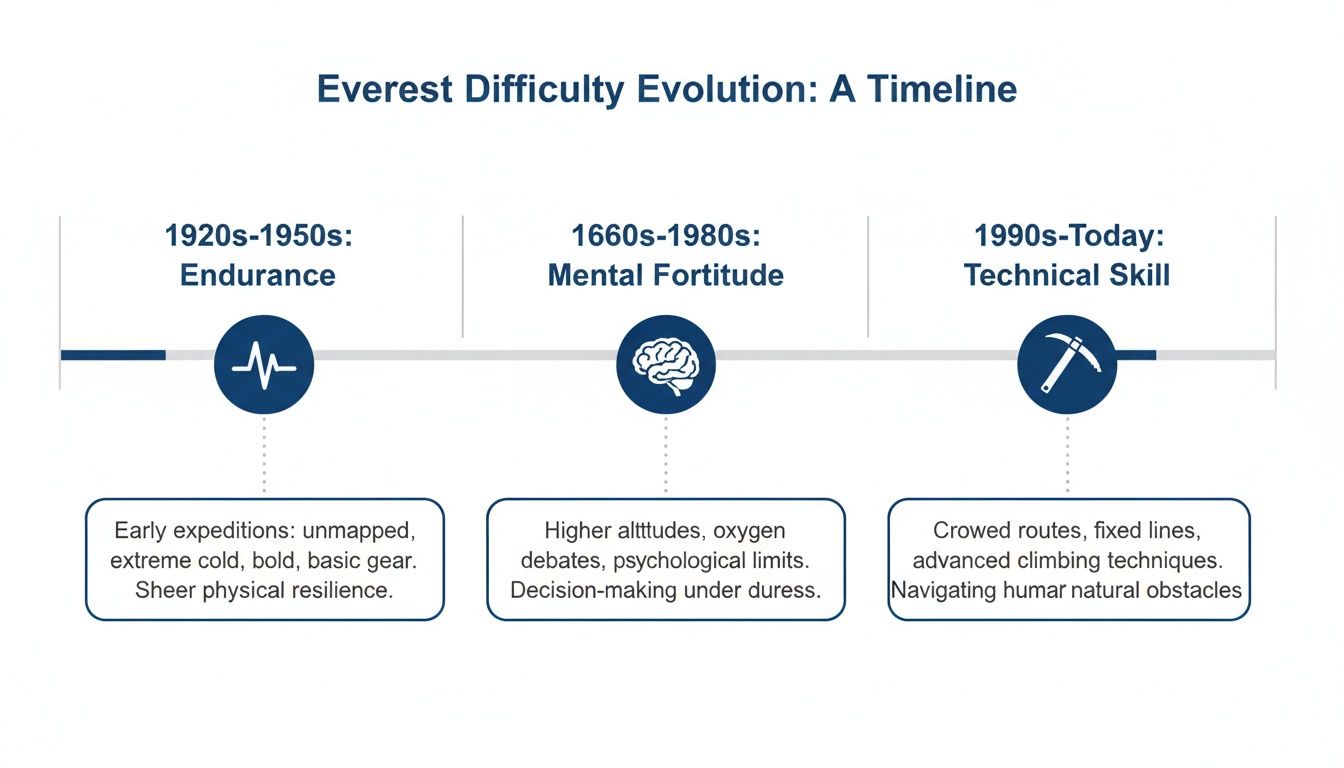

This timeline shows just how the demands shift as you climb higher, moving from pure endurance into a desperate need for mental clarity and technical precision right when your body is at its weakest.

As you can see, physical grit gets you onto the mountain, but it's sharp thinking and flawless skills that get you off it, especially when the altitude is doing its best to take those things away from you.

The Art of Acclimatisation

So, how do you survive this? Through a long, gruelling, and absolutely critical process of acclimatisation. The golden rule is simple: climb high, sleep low . This means spending weeks doing 'rotations' up and down the mountain from Base Camp.

You might climb through the treacherous Khumbu Icefall to Camp I, push on to Camp II, spend a night or two in the thin air, and then descend all the way back to Base Camp to recover. It’s a slow, monotonous, and draining cycle, but each rotation forces your body to adapt by producing more red blood cells to carry what little oxygen is available.

Acclimatisation is the foundation upon which a safe summit attempt is built. Rushing this process is one of the most common and dangerous mistakes a climber can make. It is an unavoidable investment of time and energy.

The Silent Killers: HAPE and HACE

Even with the most patient acclimatisation schedule, two severe forms of altitude sickness are a constant threat. They are the mountain's silent killers.

- High-Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE): This is when fluid leaks into your lungs. It feels like drowning from the inside out, causing breathlessness, a rattling cough, and total exhaustion. Immediate descent is the only cure; without it, HAPE is often fatal.

- High-Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE): Here, fluid leaks into the brain, causing it to swell. The symptoms are terrifying: confusion, stumbling, severe headaches, and loss of coordination (ataxia). HACE is a full-blown medical emergency requiring immediate descent and oxygen.

Understanding these physiological realities is the first step to truly grasping why Everest is so hard. It’s a biological exam that pushes the human body to its absolute limits. You can train for it, but you can never truly beat it. This internal war is the silent backdrop to every single step taken on the mountain. To dig deeper, read our guide on training for the unknown to prepare your mind and body.

Navigating the Mountain's Objective Dangers

Beyond the internal, physiological war happening inside your body, an Everest climb is an exercise in navigating an environment of immense and impartial hazards. These are the mountain’s objective dangers —risks that exist regardless of your fitness, experience, or willpower.

Sound judgement, technical skill, and a deep respect for the terrain are the only tools that offer any real defence.

On the standard South Col route from Nepal, this education begins almost immediately after leaving Base Camp. Your first major hurdle isn’t a vertical wall, but a chaotic, frozen river of ice moving downhill at roughly one metre per day . Welcome to the Icefall.

The Khumbu Icefall

The Khumbu Icefall is, without a doubt, one of the most dangerous and technically demanding sections of the entire climb. It's a two-kilometre-long maze of shifting ice, where towering blocks called seracs —some the size of small buildings—can collapse without a moment's notice.

Deep, gaping crevasses slice through the entire area, many hidden beneath deceptively thin snow bridges.

To make a route possible, a specialist team of Sherpas known as the ‘Icefall Doctors’ arrives at the start of each season. They fix a network of ropes and aluminium ladders, some spanning terrifyingly deep chasms, which every climber must then use.

Moving through the Icefall is a calculated risk. It's typically done in the pre-dawn cold when the ice is most stable. Efficiency is everything; the goal is to minimise your time in this unstable, ever-changing zone.

The Icefall is a place you cannot afford a mistake. It demands total concentration and fluid movement. It’s a stark reminder that you don't fight nature here; you move carefully within its powerful systems, always aware that you are merely a guest.

The Lhotse Face

After navigating the relative flatness of the Western Cwm beyond the Icefall, climbers face the next great technical challenge: the Lhotse Face. This is a formidable, 1,125-metre (3,700-foot) wall of hard, glacial blue ice, angled at a relentless 40 to 50 degrees , and sometimes even steeper.

Ascending this sheer face requires complete proficiency with crampons and ice axes. Climbers move up fixed ropes using a mechanical ascender, or Jumar, whilst their crampons bite into the hard ice below.

It is a gruelling, calf-burning ascent that can take many hours, all performed at an altitude above 7,000 metres .

The Lhotse Face is also a notorious funnel for rockfall and ice dislodged by teams higher up. Its vast, open expanse leaves climbers exposed to the full force of the wind, making progress slow, draining, and incredibly cold. This section tests not just skill but pure, physical endurance at an altitude where every single movement is a monumental effort.

Avalanches and Unpredictable Weather

The threat of avalanches is a constant presence on Everest. They can be triggered by new snowfall, wind loading on slopes, or the sudden collapse of seracs. The Khumbu Icefall and the slopes leading to Camp III on the Lhotse Face are particularly vulnerable.

And then there's the weather.

Whilst modern forecasting has significantly improved safety, allowing teams to plan summit pushes during brief windows of calm, the mountain generates its own microclimate. Conditions can change with terrifying speed.

High winds, especially from the jet stream, can make the summit ridge utterly impassable. A sudden snowstorm can obliterate the route and trap climbers high on the mountain, turning a summit bid into a fight for survival.

Understanding these external dangers is crucial. Climbing Everest isn’t just about battling your own physical limits; it’s about skilfully navigating a landscape of profound and ever-present risk.

Success and Failure by the Numbers

To really get your head around how hard it is to climb Mount Everest, you have to look past the stories and face the sober reality of the numbers. Data gives us a clear, cold measure of the challenge, grounding the whole conversation in fact, not feeling. And whilst modern logistics, guiding, and weather forecasting have definitely tipped the odds in our favour, the figures still paint a picture of a profoundly difficult undertaking.

A summit is never guaranteed. It doesn't matter how much you've prepared or how much you've spent; the mountain always gets the final vote. A truly successful expedition is often defined not by reaching the top, but by making the right call to turn back and get down safely. That’s the quiet authority earned through experience—knowing when you’re being determined and when you’re just being stubborn.

Looking at the Summit Stats

Over the last few decades, the chances of actually getting to the summit have improved dramatically. Success rates have almost doubled, jumping from around 30% in the 1990s to nearly 60% by the 2010s. This is a direct result of better operational support and all the hard-won knowledge we've accumulated.

Looking at the data from 2006 to 2019, roughly two-thirds of climbers who made it past Base Camp successfully reached the top. Interestingly, the stats show a slight difference between the sexes, with 68.2% of women and 64.4% of men summiting during this time. But it's easy for these big-picture numbers to be a bit misleading; they hide the huge differences you see depending on which route you take. You can find out more about how many people have climbed Mount Everest and get a deeper look at these stats.

Why Climbers Turn Around

A summit rate of 60-65% also means that more than a third of attempts end before the top. Turning back isn't a sign of weakness; it's often the strongest and hardest decision a climber can make. The reasons people turn around are varied, and they really highlight just how many things can go wrong:

- The Body Gives Up: The most common reason is simple: the body just cannot handle the extreme altitude. This might show up as a sudden illness, sheer exhaustion, or the terrifying first signs of HAPE or HACE.

- The Weather Window Slams Shut: The brief period of good weather needed for a summit push can vanish with almost no warning. High winds, unexpected storms, or deep snow can make that final climb impossibly dangerous.

- Gear Failure: In a place where temperatures can plummet to -35°C , a broken oxygen regulator or a snapped crampon isn't a small problem—it's a life-threatening emergency.

- Pacing and Time: Every summit push is a race against the clock. Move too slowly, and you risk running out of bottled oxygen or getting caught by darkness high on the mountain, forcing a retreat.

The numbers tell a clear story. Success is more achievable now than ever, but it's still a long way from being a sure thing. The mountain demands respect, and a huge number of well-prepared climbers will, for reasons often totally out of their control, have to turn for home before ever reaching their goal.

The Unseen Challenges of an Everest Expedition

Climbing Everest isn't just a physical battle. It's a life project. The parts you don't always hear about—the logistics, the cost, the sheer mental grind—are just as tough as any crevasse or icefall.

Thinking about an Everest expedition as a simple transaction for a summit ticket is a mistake. It’s an investment in a massive, incredibly complex operation that makes the climb even possible.

The Financial Mountain

One of the first questions we get is always about the cost, and the numbers can be a real shock. A fully supported, guided commercial expedition can run anywhere from £35,000 to well over £100,000 . That price tag isn’t just for a guide’s time. It covers a colossal support system that’s working behind the scenes.

This investment includes:

- Permits: The climbing permit from the Nepalese government alone will set you back thousands of pounds.

- Logistics: This covers everything from the hair-raising flight into Lukla (2,860m) to the yaks and porters needed to haul tonnes of gear up to Base Camp.

- Sherpa Support: You’re backed by a team of exceptionally skilled Climbing Sherpas who fix the ropes, set up the high camps, and carry critical supplies like oxygen and tents.

- Oxygen Systems: The price includes multiple bottles of supplementary oxygen and the sophisticated regulator systems required to use them safely above 8,000 metres.

- Base Camp Life: For two months, a small, temporary city becomes your home, complete with cooks, communications systems, and medical support.

Getting your head around these financial realities is a critical first step. The cost is a direct reflection of the scale of the operation and the level of risk management involved.

The Mental Game

The psychological commitment is every bit as demanding as the physical and financial ones. An Everest expedition is a two-month mental marathon, where the biggest fights are often waged inside your own head, inside your own tent.

The strain starts early, with the monotony of life at Base Camp. Days are a cycle of acclimatisation hikes, rest, and a whole lot of waiting. Just keeping your focus and morale up during these long, repetitive periods is a huge challenge in itself.

The mind has to be trained just as rigorously as the body. Under extreme fatigue and hypoxia, your decision-making is shot. The ability to stay calm, assess a situation that’s changing by the minute, and make a sound call—especially the call to turn back—is the single most important skill any climber can have.

That pressure ramps up intensely when the summit window arrives, which might only be a few short days. After weeks of hard work and waiting, the success of the entire expedition comes down to this brief period. It creates an immense psychological burden, where the temptation to push on against your better judgement can be overwhelming.

The Ultimate Decision

The hardest choice any climber on Everest ever makes is the decision to turn around before reaching the summit. It takes a kind of mental strength that’s difficult to fully grasp until you’re there. It means accepting that despite years of training and a huge financial investment, today just isn’t the day.

This isn’t failure. It’s the mark of a smart, seasoned mountaineer who understands that the summit is optional, but getting down is mandatory.

The numbers tell a sobering story. To date, 335 people have died on Everest , which works out to about 1.11 deaths per 100 climbers . The descent has proven to be far deadlier than the ascent, a stark reminder that reaching the top is only halfway. This reality underscores why turning around, saving your energy and mental sharpness for the dangerous journey down, is often the wisest—and toughest—decision of all.

Building the Right Experience for an 8000-metre Peak

An 8000-metre peak is not the place for ambition to get ahead of ability. To have any realistic chance of not just standing on the summit but getting back down safely, a climber has to go through a multi-year apprenticeship. Everest should never be your first big mountain; it should be the final exam after a long, deliberate journey of learning the craft.

This journey isn't about ticking off summits. It’s about methodically building a bedrock of technical skill, resilience at high altitude, and solid judgement in places where the consequences of a mistake are far less severe. Our entire philosophy is built on this: we don't fight nature, we learn to live within its rules. That process starts years before you ever see the Khumbu.

The Foundational Skills

Everything begins with solid winter mountaineering skills. Before you even think about the Himalayas, you need to be completely at home with the fundamental tools of the trade. This means building a strong base in environments that are challenging but won't kill you for a simple error.

- Scottish Winter or the European Alps: These are the perfect classrooms. It’s here you’ll truly master crampon work on steep ice, practise ice axe self-arrest until it’s pure muscle memory, and get slick with rope systems and crevasse rescue drills.

- Systems Mastery: This is also where you dial in your personal systems. You learn how to layer your clothing perfectly to manage sweat and stay warm, develop a tent routine in your Hilleberg so smooth you can do it in a blizzard, and master your stove in freezing conditions.

Think of these skills as the grammar of mountaineering. Without them, you cannot hope to understand the complex language of a mountain like Everest. A brilliant way to get started is by joining a proper expedition training course where you learn these skills from seasoned professionals.

Stepping Up to High Altitude

Once those core skills are second nature, it's time to test them higher up. The physical and mental pressure above 6,000 metres is a world away from anything you'll experience in the Alps. This is where you find out how your body really copes with thin air.

This is why intermediate objectives are so important. Peaks like Aconcagua in Argentina ( 6,961 metres ) or Denali in Alaska ( 6,190 metres ) are the ideal testing grounds. They are major expeditions in their own right, demanding weeks of your life and exposing you to serious altitude and bitter cold, but without the unique dangers of things like the Khumbu Icefall.

On these mountains, you gain priceless experience in carrying heavy loads, pacing yourself over weeks, and making clear-headed decisions when your body and brain are starved of oxygen. It’s where you prove you can pull your weight and function as part of a team in a seriously demanding, high-altitude world.

The Right Physical Preparation

Throughout this multi-year journey, your physical conditioning is the constant hum in the background. The strength you need for Everest isn't about gym PBs; it’s about gritty endurance and the ability to just keep going. To prepare your body for the unique grind of an 8000-metre peak, you must incorporate functional strength training into your routine. This builds the real-world strength required for hauling a heavy pack up steep slopes, day after day.

The history of British mountaineering on Everest proves how this long-term preparation pays off. Kenton Cool holds the British record with an incredible 17 ascents, showing that with exceptional skill and experience, repeated success is achievable. This legacy began with the very first successful ascent on 29 May 1953 , led by British expedition leader Lord John Hunt. These achievements show that whilst Everest is brutally hard, it is within reach for those who treat the mountain—and the journey to get there—with the respect it demands.

The path to an 8000-metre peak is methodical and patient. Each preceding climb is a lesson in skill, a test of physiology, and an education in judgement. By the time a climber is ready for Everest, the summit is not a distant dream, but the logical next step in a well-travelled journey.

Your Everest Questions, Answered

Over the years, we’ve found that whilst every climber’s path is their own, the big questions about taking on Everest tend to be the same. Here are the straight answers to the questions we hear most often.

Just How Fit Do You Need to Be?

You need a formidable engine. Think of it as the ability to push hard, uphill, with a heavy pack, for 8-12 hours a day—and then get up and do it again the next day. It’s a specific kind of endurance that goes way beyond marathon fitness.

But fitness is only half the story. The real wild card is how your individual body copes with extreme altitude. You can be the fittest person on the mountain, but if your body does not acclimatise well, it counts for nothing.

Can a Beginner Climb Mount Everest?

In a word: no.

To attempt Everest with any degree of safety, you need a deep and practical knowledge of winter mountaineering. That means being completely at home with an ice axe and crampons, and having your rope skills dialled in.

Crucially, you must have experience on other big mountains, ideally over 6,000 metres . Everest is the culmination of a long climbing apprenticeship, not the place you go to start it.

What’s the Hardest Part of the Climb?

Ask ten climbers, and you might get ten different answers, but most of the challenges fall into one of three buckets.

- The Physical Grind: Simply functioning in the ‘Death Zone’ above 8,000 metres is an unbelievable strain. Every single step is a monumental effort, pushing your body to its absolute limit.

- The Objective Danger: For many, the sheer stress of navigating the Khumbu Icefall is the most terrifying part. It’s an unstable, ever-shifting maze of ice, and you’re completely at the mercy of the mountain.

- The Mental Game: The sheer length of the expedition is a huge factor. You’re on the mountain for two months, all of it building towards one short, intense summit window. Managing the pressure, boredom, and anxiety for that long is, for many, the toughest challenge of all.

How Much Does It Really Cost?

For a well-run, reputable expedition on the south side, you should expect to budget anywhere from £35,000 to over £100,000 .

That figure buys you permits, a huge logistical operation, world-class Sherpa support, bottled oxygen, food, and specialised high-altitude gear. The massive price range comes down to the level of support, guide-to-client ratios, and the overall safety standards of the organisation you choose.

At Pole to Pole , we believe the journey to a peak like Everest begins years earlier. It starts with building foundational skills and a deep respect for the high mountains. Our expedition training courses are designed to build the competence and mindset required for the world's greatest challenges. Explore our training programmes to start your journey.