A Guide to Animal Life in Antarctica

It is easy to picture Antarctica as a silent, empty world of white. A dead continent. But that is a profound misunderstanding.

The truth is, the continent and its surrounding Southern Ocean are pulsing with life. It is a resilient, highly adapted ecosystem, a testament to survival in one of the most extreme environments on Earth. From the chaotic energy of a vast penguin colony to the silent, colossal presence of a whale, the animal life in Antarctica is unlike anything else you will ever witness.

The Thriving Heart of a Frozen Continent

To the unprepared eye, Antarctica is ice and rock. An expeditioner, however, learns to read the landscape differently, to see the subtle signs of a dynamic reality unfolding at the continent's edge and within its frigid waters.

You learn to spot the distant blow from a Humpback whale. The dark, sleeping shape of a Weddell seal near its breathing hole. The faint pink colouration of the sea, revealing a massive swarm of krill just below the surface.

This is not a chaotic free-for-all. It is a finely balanced system, built on an immense foundation. Understanding this intricate web of life is not just an academic exercise—it is a fundamental responsibility for anyone privileged enough to set foot here. This place has a quiet authority that demands respect.

Our journey into Antarctic wildlife will focus on the key pillars of this ecosystem:

- The Foundation Species: Antarctic krill, the tiny crustacean that acts as the engine for almost all life in the Southern Ocean.

- The Icons of the Ice: The various penguin species, from the steadfast Emperor to the bustling Adélie, each with its own incredible story of survival.

- Masters of the Pack Ice: The six species of seal that have mastered life both in the water and hauled out on the shifting ice.

- The Ocean Giants: The whales and diverse seabirds that travel vast distances to feast in these incredibly productive waters.

Each of these groups plays a crucial role in a food web that is both robust and surprisingly fragile. An appreciation for this begins with recognising a strange paradox: whilst Antarctica's interior is the world's largest desert, its coastlines and ocean are anything but empty. You can learn more about this in our article explaining why Antarctica is considered a desert.

For those who travel here, witnessing the animal life in Antarctica is a primary goal. It is also a powerful reminder that we are merely visitors in their domain.

Understanding the Engine of the Southern Ocean

At the very bottom of the entire Antarctic food web, you will find a tiny, shrimp-like crustacean: the Antarctic krill ( Euphausia superba ). To understand this place, you have to start with them. Do not think of krill as just another species. Think of them as the central engine powering almost every living thing in the Southern Ocean.

Their sheer numbers are staggering. They form immense, pinkish-red swarms so vast they can colour the water, visible from the deck of a ship. These swarms are the primary food source for everything from an Adélie penguin to the colossal blue whale. When you see one on an expedition, you are getting a direct visual cue of the ecosystem's health. It is the pulse of the continent, made visible.

Individually, these creatures are only a few centimetres long. But together, they form one of the largest single-species biomasses on the entire planet. Their whole life is tied to the sea ice, which gives their larvae crucial shelter and a food source—ice algae—to survive the brutal winter months.

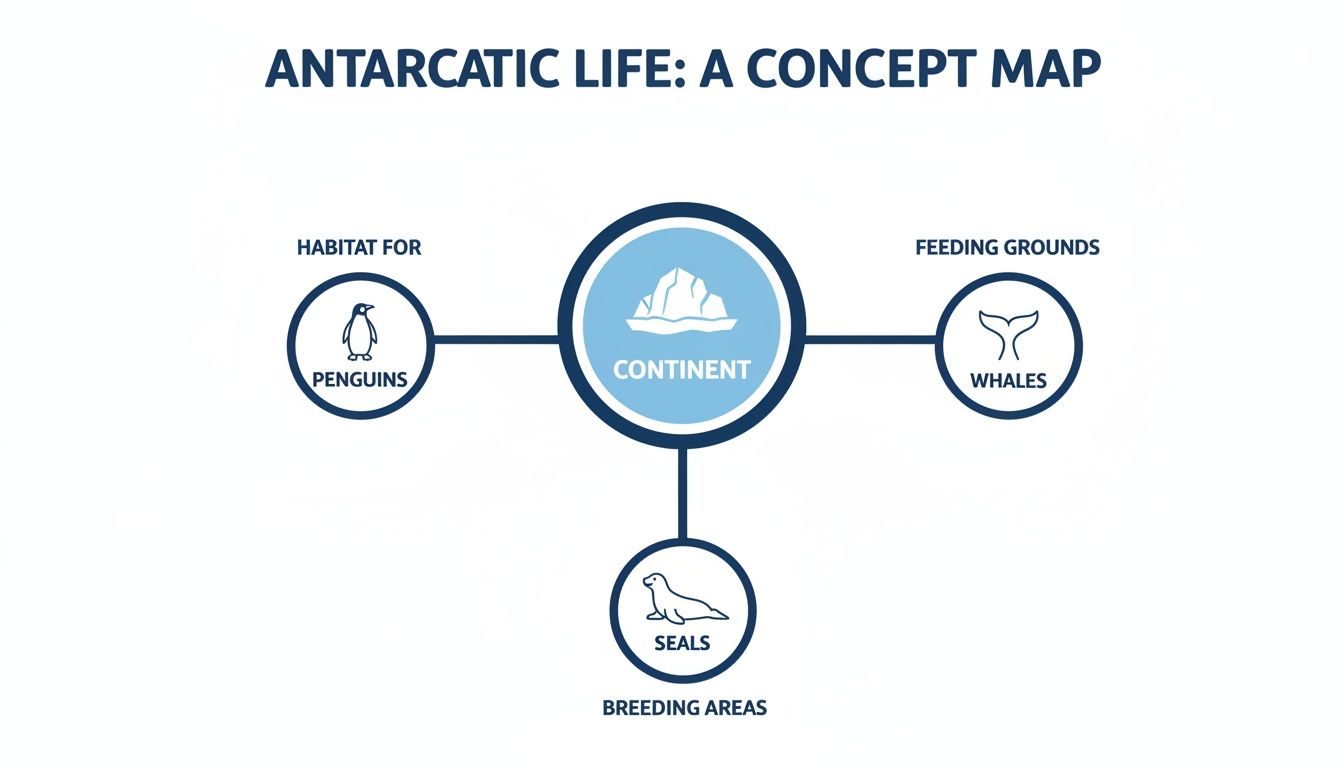

This map shows just how central these tiny creatures are to the major animal groups in Antarctica.

You can see it clearly: penguins, whales, and seals all point back to this single, foundational part of the food web.

The Keystone Species of the South

We use the term keystone species for an organism that essentially holds an entire ecosystem together. Take it away, and the whole system either changes dramatically or collapses completely. In the Southern Ocean, krill are the undisputed keystone.

It is difficult to overstate their importance. They are the critical link, taking the energy from microscopic marine algae—phytoplankton—and converting it into a protein-rich meal that bigger animals can eat. Without that vital energy transfer, the giants of Antarctica simply could not survive here.

This reliance on a single species creates a system that is both incredibly efficient and incredibly fragile. Any changes to sea ice cover or ocean temperatures hit the krill population hard, sending shockwaves right up the food chain.

The numbers behind this tiny creature’s impact are almost unbelievable. They truly are the engine of this polar world.

Antarctic Krill: The Engine of the Southern Ocean

| Metric | Statistic | Ecological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Total Biomass | Estimated 300-500 million tonnes | One of the largest single-species biomasses on Earth, forming the foundation of the food web. |

| Primary Consumer | Feeds on phytoplankton and ice algae | Converts microscopic plant energy into a usable food source for larger animals. |

| Primary Food Source | 85% of a crabeater seal's diet | Direct, critical food source for most seal species, including crabeater, leopard, and fur seals. |

| Whale Sustenance | A single blue whale can eat up to 4 tonnes per day | Fuels the annual migration and survival of baleen whales like humpbacks, fins, and blues. |

| Penguin Diet | Constitutes up to 90% of the diet for Adélie and chinstrap penguins | Essential for breeding success and chick survival for multiple penguin species. |

This incredible biomass is not just an abstract number; it is the living, breathing fuel that makes every whale sighting and every bustling penguin colony possible.

Seasonal Movements and Expeditionary Relevance

Krill do not just stay in one place. Their location shifts dramatically with the seasons. During the austral summer, from November to March, the days get longer and the sea ice retreats, triggering enormous phytoplankton blooms. This is when krill populations explode, creating the rich feeding grounds that draw whales on their long migrations south to the Antarctic Peninsula.

For anyone on an expedition, understanding this seasonal rhythm is everything. A sighting of lunge-feeding humpbacks is not a random event. It is the climax of a story involving ocean currents, sunlight, and the life cycle of a tiny crustacean. It connects you to the deep, powerful mechanics of the environment.

Witnessing this spectacle requires a similar level of commitment and understanding as that needed for our own demanding ocean-going challenges. The Southern Ocean does not give up its secrets easily. It rewards patience, and it rewards knowledge.

Penguins: The Icons of the Ice

When you picture Antarctica, you almost certainly picture a penguin. It is unavoidable. But these birds are far more than symbols; they are masters of this place, the living embodiment of the resilience it takes to thrive where so few others can.

To an expeditioner, penguins are a constant, compelling presence. Their formal, almost comical appearance hides a tough, determined character shaped by millennia of survival. An encounter with a bustling colony is an experience that stays with you—a chaotic, noisy, and pungent reminder that life here does not just survive. It flourishes.

The Major Species You Will Encounter

On expeditions, especially around the Antarctic Peninsula, you will mainly run into four key species. Each has its own distinct personality and its own strategy for mastering the continent’s demands.

- Adélie Penguin: Small, feisty, and endlessly busy. The Adélie is a true Antarctic specialist, the one you will see comically stealing pebbles from a neighbour’s nest to build up its own.

- Chinstrap Penguin: You cannot miss the thin black line under their beaks. Chinstraps often nest on steep, rocky slopes, seemingly defying gravity as they clamber to and from the sea.

- Gentoo Penguin: The largest of the brush-tailed penguins, Gentoos are easy to spot by the white patches above their eyes. They tend to be a little less aggressive than Adélies and often form large, accessible colonies.

- Emperor Penguin: The most formidable of them all. Standing nearly 1.2 metres tall (4 feet) , they endure the brutal Antarctic winter to breed—a feat of endurance that is difficult to grasp until you have felt that cold for yourself. A sighting is a rare privilege, as their breeding grounds are far south, like the colony at Snow Hill Island (64°30′S 57°30′W).

Seeing a lone Emperor on an ice floe is a moment of quiet reverence. It is a testament to the sheer fortitude required just to exist here.

Colony Life and Adaptations

Penguin colonies are not just random gatherings; they are highly organised societies, governed by the strict timetable of the short Antarctic summer. From November, the birds arrive to claim territory, build nests (mostly simple circles of stones), and perform their unique courtship rituals.

Their physiology is just as remarkable. A dense layer of insulating feathers, a hefty fat reserve, and a clever circulatory system in their feet all work together to minimise heat loss. In the water, they transform into powerful, streamlined swimmers, pursuing krill and fish with incredible agility.

Witnessing this efficiency firsthand changes your perspective. It is a powerful lesson in purposeful design, where every feature serves a critical function. There is no wasted energy.

An expeditioner quickly learns to read the subtle social dynamics of a colony. You see the constant negotiation for space, the diligent care of eggs and chicks, and the ever-present threat from predatory skuas circling overhead. It is an entire world operating on instinct and necessity.

A Legacy of Observation

Watching these colonies is not new. In fact, some of the most striking historical data comes from the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) during the International Geophysical Year of 1957-1958 . Early scientists logged over 10,000 breeding pairs of Adélie penguins near the Peninsula, discovering densities of up to 5,000 nests per kilometre of coastline.

Those early counts provided a vital baseline for understanding Antarctic wildlife. This legacy of careful observation, pioneered by explorers like Robert Falcon Scott and Ernest Shackleton, informs everything we do today. Our presence must be managed with precision and respect.

Expedition Protocol: A Matter of Respect

The International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators (IAATO) sets firm guidelines for all visitors. These are not suggestions; they are rules we live by.

- Maintain Distance: A minimum distance of 5 metres (16 feet) must be kept from penguins at all times. If a penguin waddles up to you, you stand still and let it pass.

- Do Not Block Their Path: Penguins have established "highways" they use to travel between their nests and the sea. Never stand on or obstruct these tracks.

- Observe Quietly: Loud noises cause stress. We move slowly and speak in low tones, minimising our impact on their natural behaviour.

Following these protocols is the most fundamental way we show respect for this environment. We are temporary guests in their home. And if you are particularly drawn to these iconic birds, you might also be interested in exploring various penguin-themed products.

Observing penguins is more than just wildlife watching. It is an opportunity to witness raw, unfiltered nature and to understand the discipline required to not only survive but thrive in the most demanding place on Earth.

Seals: Masters of the Pack Ice

Penguins might be the poster children of Antarctica, but seals are the true masters of the pack ice.

Seeing a seal hauled out on an ice floe is watching a creature perfectly at home. It is a living example of the Pole to Pole philosophy: learning to live in nature, not fight against it. Six species call this region home, and each one is a masterclass in survival.

Learning to tell them apart and understand their behaviour is not just about ticking off a list. It is about learning to read the environment and move through it with quiet respect.

The True Seals of the Southern Ocean

Four of the six species you will find here are from the Phocidae family—the ‘true seals’. These are the classic Antarctic seals, the ones you will often find sprawled out on the sea ice, soaking up the pale sun.

- Weddell Seal: Easily the most placid and approachable seal, the Weddell is the southernmost breeding mammal on Earth. They are experts of the fast ice, using their teeth to grind breathing holes through ice up to two metres thick. This skill allows them to stay put and survive the harshest winters.

- Crabeater Seal: Do not let the name fool you; crabeater seals almost exclusively eat Antarctic krill. They have some of the most intricate teeth in the animal kingdom, shaped with unique lobes that work like a sieve, filtering mouthfuls of krill from the icy water.

- Leopard Seal: The undisputed top predator of the pack ice. Long, powerful, and almost reptilian in its movement, the Leopard seal is a formidable hunter. Watching one patrol the edge of an ice floe is a raw reminder that this ecosystem is built on an unforgiving food chain.

- Ross Seal: The most mysterious of the lot. Ross seals are rarely seen, preferring the dense, almost impenetrable pack ice. With their small heads and strange, trilling calls, an encounter with one is a genuine privilege.

The Eared Seals

The other two species belong to the Otariidae family, or ‘eared seals’. You can spot them by their visible external ear flaps and their ability to ‘walk’ on land by rotating their large front flippers forward.

- Antarctic Fur Seal: Hunted almost to extinction in the 19th century, these seals have made an astonishing comeback. You will now find enormous breeding colonies on islands like South Georgia, a place made famous by Shackleton’s epic crossing. They are agile, noisy, and fiercely territorial.

- Southern Elephant Seal: The absolute giant of the seal world. Males, or ‘beachmasters’, can weigh a staggering 4,000 kilograms (8,800 pounds) . They are famous for the brutal, dramatic battles between males fighting to control huge harems of females on sub-Antarctic beaches.

A History of Overwhelming Numbers

It is difficult to comprehend just how many of these animals there are.

Old records from the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) at Signy Research Station, which has been running since 1947 , give us a clue. After the organisation was renamed in 1962 , observers started noting astonishing numbers—peak sightings of 25,000 crabeater seals in the South Orkney Islands area alone during a single summer.

These sightings were just a fraction of the total population. UK surveys in the 1970s estimated the global crabeater population was over 15 million . You can explore the history of the British Antarctic Survey to learn more about this foundational research.

This is not just a collection of different animals; it is a spectrum of survival strategies. From the krill-filtering specialist to the apex predator, each seal has carved out a precise niche in the ecosystem. Their resilience is a powerful lesson in adaptation.

Moving Amongst the Masters

On any expedition, you will likely see seals hauled out on ice floes, looking completely indifferent to your presence. But do not mistake this for an invitation to get closer.

Just like penguins, seals have the right of way. It is our absolute responsibility to give them a wide berth.

Understanding their behaviour is crucial. A seal lifting its head to watch you is aware of you. A yawn or a slight shift in position can be a sign of stress. The goal is always to pass by without causing any change in their natural behaviour. We are temporary visitors in a world they have mastered over millennia.

Whales and Seabirds: Giants of the Southern Ocean

Antarctica’s story is not confined to the ice. The Southern Ocean is a seasonal home to some of the planet’s most magnificent creatures, drawn here by the incredible productivity of the water.

Seeing one is never a guarantee. That is what makes every encounter a genuine privilege.

The sudden spray from a Humpback’s blowhole or the effortless glide of a Wandering Albatross is a powerful reminder of the sheer scale of this ecosystem. These are not static exhibits; they are dynamic, transient giants in a vast, interconnected world.

The Great Whales of the Southern Ocean

For several whale species, these icy waters are a critical feeding ground. They travel thousands of kilometres from warmer breeding grounds just to feast on the seasonal abundance of krill.

From the deck of an expedition vessel or a Zodiac, identifying them comes down to a few key signs: the shape of a dorsal fin slicing through the water, the unique pattern on a fluke as it disappears below, or the height and shape of the misty blow.

- Humpback Whale: Often the most acrobatic of the bunch, Humpbacks are famous for breaching clear out of the water and slapping their powerful tails. They are lunge-feeders, sometimes seen working together to herd krill before surfacing with huge, gaping mouths.

- Minke Whale: Smaller, faster, and far more elusive. The Minke is often just a fleeting glimpse—a sharp, curved dorsal fin breaking the surface before it vanishes again. Tracking them amongst the ice floes is a true challenge.

- Orca (Killer Whale): The apex predator of the Southern Ocean. Orcas here are incredibly intelligent pack hunters, with different family groups, or ecotypes, specialising in hunting seals, fish, or even other whales using sophisticated, coordinated tactics.

A whale sighting is a lesson in patience. It means scanning the horizon, listening for the sound of a blow, and understanding that you are observing them entirely on their terms.

Avian Life Beyond Penguins

Whilst penguins get most of the attention, the skies above the Southern Ocean are patrolled by a remarkable diversity of other seabirds. These birds are masters of long-distance flight, perfectly adapted to a life spent almost entirely at sea.

Their presence is a constant companion on any voyage south. Learning to identify them adds a whole new layer of appreciation for this environment.

- Petrels and Shearwaters: These birds are expert gliders, often seen skimming just inches above the waves, using the wind currents to their advantage. The Southern Giant Petrel is a particularly imposing sight, a powerful scavenger often found near seal and penguin colonies.

- Skuas: Bold, intelligent, and opportunistic. Skuas are the pirates of the Antarctic, often seen harassing other birds to steal their catch or preying on unguarded penguin eggs and chicks.

- Albatrosses: To see a Wandering Albatross in flight is to witness aerodynamic perfection. With a wingspan that can exceed 3.5 metres (11 feet) , they travel immense distances with barely a flap, locking their wing joints to soar on the ocean winds for hours.

To watch an albatross navigate the fierce winds of the Southern Ocean is a lesson in efficiency. It does not fight the gales; it uses them. It is a quiet, powerful demonstration of working with the environment, not against it.

A Legacy of Ornithological Records

This incredible diversity of avian life has fascinated scientists for decades. Compelling data from the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) highlights this long history of observation. During the peak of the International Geophysical Year in 1958/59 , ornithological surveys across British stations tallied 12 species, including an incredible 8,000 pairs of chinstrap penguins.

Observing these giants of the ocean and sky is not just about ticking species off a list. It is about understanding their place in the greater Antarctic system and recognising the immense journeys they undertake to be here. Each one is a testament to the richness of an ocean that, from a distance, can seem deceptively empty.

Observing Antarctic Wildlife Responsibly

To set foot in Antarctica is a privilege, not a right. The entire experience hinges on one simple, non-negotiable principle: we are visitors here, and our presence should be almost undetectable. The most important responsibility we carry is a profound respect for the animal life in Antarctica.

This is not just a nice idea. It is a discipline, grounded in the Antarctic Treaty System and the strict operational guidelines laid out by the International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators (IAATO). These rules are not suggestions; they are the absolute foundation of how we move through this incredible place.

The Art of Keeping Your Distance

The single most important rule is about distance. For every animal here, energy is the currency of survival. If you cause an animal to move or even just change its behaviour, you have forced it to spend that precious currency. You have stolen a resource it needs to live.

- The 5-Metre Rule: For penguins, you must stay at least 5 metres (16 feet) away. If a curious individual decides to waddle over to inspect you, your job is to stand perfectly still and let it pass on its own terms.

- The 15-Metre Rule: For seals resting on ice or land, that distance grows to 15 metres (50 feet) . Their sleepy, placid look is not an invitation to edge closer.

- Whales and Vessels: There are strict protocols for how our vessels and Zodiacs approach whales. We observe from a distance that ensures we never disturb their feeding, travelling, or socialising.

These are not random numbers. They are carefully calculated buffers, designed to keep the wildlife well inside its comfort zone and prevent the slow, cumulative stress that human presence can cause.

Reading the Unspoken Language

Real expertise is not just about following rules blindly; it is about understanding the "why" behind them. That means learning to read the quiet, subtle language of the animals themselves.

A seal lifting its head to watch your approach, a penguin suddenly changing its path to give you a wide berth, a nesting bird letting out a sharp call—these are all clear signals. You are too close. The goal is to move through their world without causing a single ripple, leaving them exactly as you found them. It is a philosophy shared by the best wildlife experiences, from Antarctica to a luxury Great Migration safari , where respect for an animal's natural behaviour is paramount.

Our role is to be a silent observer, never an active participant. We do not block an animal's path to the sea. We do not surround a creature. And we certainly never use loud noises to get its attention. This discipline is what separates a responsible ambassador from a mere tourist.

The timing of your trip also shapes what you will see and the specific sensitivities you need to be aware of. You can learn more in our guide on the best time to visit Antarctica for an expedition. Ultimately, every single action we take is weighed against one question: does this prioritise the well-being of the wildlife? The answer, always, must be yes.

Got Questions? We Have Answers

Stepping into a world as raw and wild as Antarctica means arriving with a healthy dose of curiosity and respect. Here are a few of the questions we hear most often from explorers getting ready for their journey south.

When Is the Best Time to See Wildlife?

The austral summer, from November to March , is the primary window. But do not think of it as one long season; each month is its own distinct chapter in the Antarctic story.

November is all about courtship. The penguins are busy with their elaborate rituals, setting the stage for the next generation. By December and January , the colonies are buzzing with the chaotic energy of newly hatched chicks.

Then, as February and March roll in, you will see those same chicks taking their first tentative steps towards independence. This is also when whale watching becomes particularly productive, as they feed relentlessly on krill before heading north on their migration.

Are Any of the Animals Dangerous?

Direct threats are almost unheard of. Safety is not about luck; it is about following strict protocols and maintaining a constant awareness of your surroundings. The Leopard seal is the continent's top predator, and it commands absolute respect. It is a powerful, curious animal, and we give it an exceptionally wide berth. No exceptions.

Our expeditions are built around the IAATO guidelines for a reason: they work. By never approaching wildlife and always moving calmly through their home, you eliminate any chance of a negative encounter. Our guides are experts in reading animal behaviour, ensuring every moment is as safe as it is awe-inspiring.

Why Are There No Polar Bears in Antarctica?

It is a good question, and the answer is simple: geography. Antarctica broke away from the supercontinent Gondwana millions of years ago, long before animals like polar bears existed. It has been an island continent ever since, completely cut off by the formidable Southern Ocean.

Without a land bridge, land-based mammals like bears, foxes, or wolves never had a pathway to get there. The entire ecosystem evolved without them. This isolation is precisely why penguins and seals can breed so successfully on its shores—their threats come from the sea and the sky, not from the land.

At Pole to Pole , we believe that understanding this remarkable ecosystem is as critical as any technical skill. Our expeditions are built on a foundation of respect, knowledge, and responsible conduct.

If you are ready to see this world for yourself, explore our signature challenges and training programmes at https://www.poletopole.com.