A Guide to Seeing Polar Bears in Canada Responsibly

To step into the Canadian Arctic is to enter the domain of the sea bear, Ursus maritimus.

This is not simply about spotting wildlife. It is a total immersion into an ecosystem where the apex predator sets the rules. For any expedition, whether scientist or traveller, the first principle is respect—a respect born from genuine competence. You do not conquer this environment. You learn to move within it, quietly and capably.

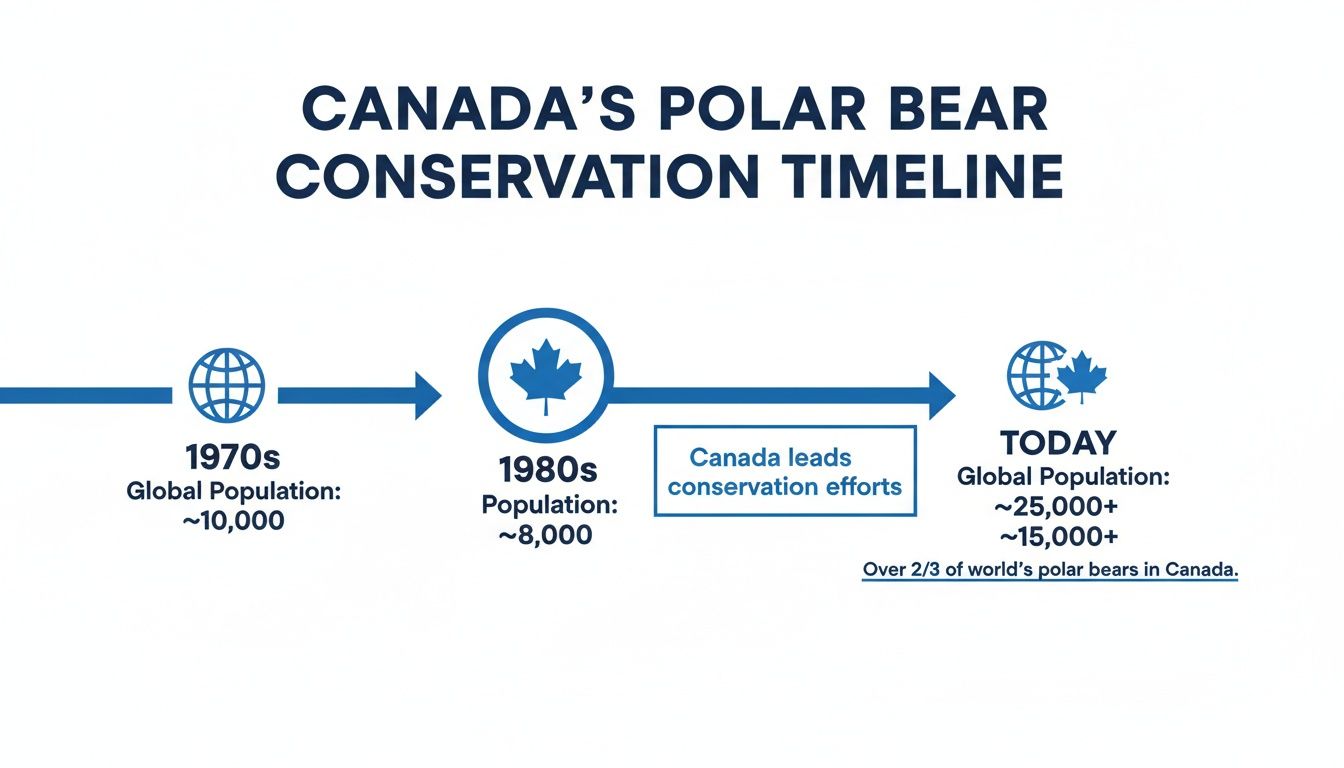

Canada is, without question, the global centre for polar bears. An estimated two-thirds of the world's entire polar bear population lives within its borders, a fact that frames the entire experience.

The Arctic Stronghold

The sheer scale is hard to grasp. We are talking about roughly 16,000 polar bears , a number that highlights Canada's immense responsibility for the species' future.

But they are not one single, monolithic group. Instead, they are managed as distinct subpopulations, each facing its own unique set of environmental pressures and opportunities across a truly vast territory. To get a real sense of this conservation framework, the data from Canada's Polar Bear Technical Committee is the place to start.

Why Subpopulations Matter

Thinking in terms of these smaller groups is absolutely critical.

A bear navigating the shifting ice of the Beaufort Sea lives a completely different reality from one waiting for the freeze-up on the coast of Hudson Bay. This approach allows for more targeted, localised conservation strategies, often developed hand-in-hand with the Indigenous communities who have shared this landscape with polar bears for millennia.

You will find these key subpopulations across several regions:

- Nunavut: This is the heartland, home to the largest number of subpopulations.

- Manitoba: Specifically, the area around Churchill, famously known as the 'Polar Bear Capital of the World'.

- Québec and Ontario: These mark the southern edges of their range along the coasts of Hudson and James Bays.

- The Northwest Territories and Yukon: This is the westernmost reach of their Canadian habitat.

This map is not static. It breathes with the seasons and, more profoundly, shifts with the long-term changes in the sea ice they need for hunting seals. For an expeditioner, accepting this fluidity is non-negotiable. We plan based on known patterns, but we are always ready to adapt to what the environment gives us on the day.

It is a discipline as vital on the ice as it is in the boardroom. Understanding this dynamic map is the first step towards a safe, respectful journey into their world.

Where And When To See Canadian Polar Bears

In the Arctic, timing is everything. It is a place that does not bend to our schedules; we must adapt to its ancient rhythms. To have any chance of a meaningful, responsible encounter with a polar bear, you have to understand the annual dance of the sea ice—the freeze and the thaw that dictates their entire world.

The most famous place to witness this is, without a doubt, Churchill, Manitoba ( 58° 46' 9" N, 94° 10' 9" W ). It has earned its title as the 'Polar Bear Capital of the World' for one very specific, very powerful reason.

The Great Churchill Gathering

Every autumn, usually from October to November , hundreds of bears from the Western Hudson Bay subpopulation find themselves drawn to the coastline near Churchill. They are not there by choice. They are waiting.

The sea ice on Hudson Bay—their primary hunting ground—has melted over the summer, forcing them ashore. For months, they have been living in a state of walking hibernation, conserving every ounce of energy and waiting for the temperature to plummet. It is this annual gathering, this tense period of anticipation, that creates the most reliable and accessible polar bear viewing on the planet. This is when specialised tundra vehicles can bring us into their world, allowing for close, safe observation without disturbing them.

From an expedition leader’s perspective, this window is a study in patience—both for the bears and for us. They are waiting for their hunting season to begin, and we are there to witness that critical moment when the ice finally solidifies and allows them to return to their true element.

This incredible natural event is set against a backdrop of decades-long conservation efforts. Canada's role has been absolutely critical.

As the infographic shows, this is not a new fight. It is a long-term commitment born from the realisation that Canada is the steward for the vast majority of the world's polar bears.

To help you visualise the best times to go, we have put together a quick guide.

Seasonal Polar Bear Viewing Opportunities In Canada

| Season | Primary Location(s) | Typical Bear Behaviour | Viewing Conditions & Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Autumn (Oct-Nov) | Churchill, Manitoba | Gathering along the coast, conserving energy, waiting for sea ice to form. Social interactions and sparring amongst males. | Tundra vehicle tours offer safe, ground-level viewing. High probability of sightings. Cold but generally accessible. |

| Spring (Mar-May) | Baffin Island, Nunavut; Northern Manitoba | Mothers emerge from dens with new cubs. Actively hunting seals on the sea ice. More movement and activity. | More remote. Often involves ski touring, dogsledding, or staying at land-based wilderness lodges. Higher expedition skill required. |

| Summer (Jul-Sep) | Hudson Bay coast; High Arctic islands | Ice-free in Hudson Bay, bears are ashore. In the High Arctic, they follow the retreating pack ice. Often seen swimming or on ice floes. | Boat-based tours in expedition vessels. Sightings are less predictable but offer a chance to see bears in a marine environment. |

This table shows there is more to seeing polar bears than just the famous Churchill season; it all depends on the kind of experience you are after.

Beyond The Beaten Path

Whilst Churchill is an incredible spectacle, it is not the only story. For those with a bigger appetite for raw wilderness, the territories of Nunavut and the Northwest Territories offer a profoundly different kind of encounter. It is wilder, more remote, and deeply humbling.

Out here, on places like Baffin Island or along the shores of the Beaufort Sea, viewing happens mostly in spring and summer. This is when the bears are in their element, actively hunting seals on the sea ice that remains. An expedition here is a world away from a tundra vehicle tour. It might involve:

- Small expedition vessels: Weaving through ice-choked fjords, scanning the floes for movement.

- Land-based camps: Living on the ice, which requires iron-clad safety protocols and the wisdom of local Inuit guides.

- Ski touring or dogsledding: Moving through the landscape quietly and traditionally, as part of a highly experienced team.

These journeys demand more—more skill, more preparation, more self-reliance. The focus shifts. It becomes less about guaranteed sightings and more about a complete immersion in the Arctic ecosystem, where seeing a polar bear is a powerful, earned privilege. The planning is complex, echoing the challenges of any true polar expedition. Our guide to planning a trip to Svalbard touches on many of the same principles.

Ultimately, you have to decide what you are looking for. The certainty and accessibility of the Churchill gathering? Or the profound challenge of a true Arctic expedition, where the journey is the goal and a bear sighting is the ultimate reward? They are both valid, but they require entirely different mindsets.

The Biology and Behaviour of Ursus Maritimus

To travel safely in the kingdom of the polar bear, you first have to understand the animal itself. Ursus maritimus —the sea bear—is a masterpiece of evolution, an organism shaped perfectly by the relentless demands of the high latitudes. True respect begins with knowing the profound capabilities of this apex predator.

Their genius for the cold is more than skin deep. What looks like a white coat is actually made of translucent, hollow guard hairs. These hairs not only trap air for insulation; they scatter sunlight to create that brilliant white appearance whilst letting solar radiation penetrate to the black skin underneath, maximising every scrap of warmth.

Below this, a layer of blubber up to 11 centimetres (4.5 inches) thick provides insulation. But it is much more than that. It is their primary energy reserve, a biological battery powering them through the lean summer months when the sea ice melts away. Their entire metabolism is a lesson in stark efficiency.

An Engine Built for Endurance

The polar bear’s physiology is like that of a world-class endurance athlete. They are masters of fat metabolism, converting a high-fat diet of seals into energy with incredible efficiency. This is what allows them to cover vast distances across the sea ice—sometimes over 30 kilometres (about 19 miles) in a single day—searching for their next meal.

Their primary hunting method is a study in patience and raw power. They will wait for hours by a seal's breathing hole in the ice, a behaviour known as still-hunting. Or they will use their phenomenal sense of smell to locate subnivean lairs—the snow dens where seals give birth. Their dependency on sea ice is absolute. It is their hunting platform, their mating ground, and their highway across the Arctic.

The bear does not fight the cold; it is a product of it. Every part of its biology, from its huge, furred paws that act like snowshoes to its small, rounded ears that minimise heat loss, is a solution to a problem the environment posed. This is a core principle we apply in our own training: live with the environment, do not battle against it.

This solitary nature defines much of their social structure. Outside of the mating season or mothers with cubs, polar bears are lone travellers. Interactions between them are usually brief and often tense.

The Lifecycle of a Polar Bear

A polar bear's life is governed by the rhythm of the seasons and the ice. Their journey starts in a snow den, dug deep into a drift, usually on land.

- Birth and Early Life: Cubs, typically twins, are born between November and January. They arrive blind, toothless, and weighing little more than half a kilogramme.

- Emergence: For the next three to four months, the family stays in the den. The mother does not eat, surviving entirely on her own fat reserves whilst her cubs nurse on milk that is almost 30% fat .

- Learning Independence: They emerge in the spring. For the next two to three years, the cubs remain with their mother, learning the crucial skills for survival: how to hunt seals, navigate the ice, and avoid the dangers posed by adult male bears.

This extended apprenticeship is vital. Once the cubs are on their own, the cycle starts again. It is a slow reproductive rate, which is one of the factors that makes their population so vulnerable to environmental change.

Understanding this deliberate, unhurried rhythm of life is the key to appreciating the fragility that exists alongside their immense power. A sighting is not just seeing an animal; it is witnessing a life forged by, and for, the ice.

Conservation Status and Threats to Canadian Polar Bears

Knowing a polar bear’s biology is only half the picture. To step into their world responsibly, you first have to understand the immense pressures they are up against. The conversation around their future often gets boiled down to a single, simple narrative of decline, but the reality on the ground is far more complex, shifting dramatically between different subpopulations.

From an expedition perspective, this is about developing situational awareness on a massive scale. We do not operate on assumptions. We work with the facts, region by region. And the single greatest fact, the one that overshadows everything else, is the loss of sea ice from a changing climate.

This is not some far-off threat; it is happening now. The sea ice is their entire hunting platform. Without it, they cannot effectively hunt their main food source—ringed and bearded seals. A longer ice-free season simply means a longer fast, forcing bears to survive on their fat reserves for punishing lengths of time.

The Nuanced Reality of Subpopulation Health

It is a huge mistake to paint all 13 Canadian subpopulations with the same brush. The story is not one of uniform collapse. Some populations are stable. A few might even be growing. Others, however, are under severe, undeniable stress.

Take the bears of the Southern Beaufort Sea. They have seen a sharp decline, a drop that has been directly linked to the dramatic loss of ice in their home range. But then you look at the Baffin Bay subpopulation, which straddles Nunavut and Greenland, and the picture gets more complicated. A 2016 estimate put their numbers at 2,826 bears —a notable increase from the 2,074 counted back in 1997. Of course, you have to be careful with direct comparisons, as survey methods change over time. Still, intensive joint research between 2011 and 2013 helped confirm this healthier number, and the population is now considered ‘likely stable’. You can review the official non-detriment report to dig deeper into the findings.

This variability shows just how critical localised management and research are. A conservation strategy that works for one group may be totally wrong for another a thousand kilometres away.

Assessing the health of a polar bear population is like planning an expedition. You have to look at all the variables—ice conditions, food availability, human activity—to make an informed decision. A single data point never tells the whole story.

Human-Bear Conflict and Co-management

As the sea ice retreats, polar bears are spending more time on land, bringing them closer to coastal communities. This inevitably leads to more human-bear conflict, a serious issue for the safety of local people and the welfare of the bears themselves.

This is where co-management becomes absolutely essential. Canada’s approach to conservation leans heavily on collaboration between government scientists, territorial governments, and Indigenous communities. Inuit hunters and elders hold generations of traditional ecological knowledge ( Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit ), offering an invaluable, ground-level perspective that scientific surveys alone can never capture.

This partnership is critical for:

- Setting sustainable harvest quotas: Making sure that any subsistence hunting is done responsibly and does not endanger the long-term health of a subpopulation.

- Monitoring population health: Blending scientific aerial surveys with on-the-ground observations from local experts who live and breathe this environment.

- Developing conflict reduction strategies: Putting community-based programmes in place, like local ranger patrols, to keep both people and bears safe.

The challenges facing Canada's polar bears are profound and tangled. There are no easy fixes here. But by focusing on solid science, adaptive co-management, and a clear-eyed view of regional conditions, there is a path forward. It demands the same discipline, respect, and deep understanding of the environment that any serious Arctic traveller must bring to the ice.

Protocols For Safe And Responsible Arctic Travel

Knowing how an animal behaves is one thing. Putting that knowledge into practice is what keeps you alive. In polar bear country, safety is not luck—it is the direct result of discipline, preparation, and constant situational awareness.

There is simply no room for complacency. Your best tool is prevention, making sure a close encounter never happens in the first place.

This mindset is drilled into every person at the Pole to Pole Academy. The goal is not confrontation; it is avoidance. That discipline starts the moment you step into the bear's world and does not end until you are safely out.

Maintaining A Secure Camp

Think of your camp as your lifeline. Its security is non-negotiable. A messy or poorly managed camp is an open invitation to a curious, or worse, a hungry bear. That is a situation you have to avoid at all costs.

Every action must be deliberate. Cooking and food storage are always set up well away from sleeping tents, usually downwind. All food, rubbish, and scented items—everything from toothpaste to fuel—go into bear-resistant containers. No exceptions.

In the field, we operate on a simple rule: a clean camp is a safe camp. This is not just about being tidy; it is a life-preserving protocol. Every scrap of food waste is packed out. No trace is left behind. This discipline protects us and, just as importantly, protects the wildlife from becoming accustomed to a human presence.

A solid alert system is also essential. A tripwire or infrared perimeter alarm gives you that critical early warning. This system does not replace vigilance, but it massively enhances it. Every team member needs to know the watch rotation and bear-response drills until they are pure muscle memory.

Understanding Bear Body Language

Reading a polar bear’s intent is a critical skill. It takes a calm mind and a trained eye to see the subtle cues that tell you what is going on in its head, letting you de-escalate a situation before it ever becomes a confrontation.

Key signals to watch for include:

- Curiosity: A bear approaching slowly with its head up, stopping often to sniff the air, is usually just checking you out. It is assessing the situation.

- Stress or Agitation: Hissing, jaw-clacking, and deep "chuffing" sounds are clear warnings. The bear feels threatened and is telling you to back off.

- Predatory Interest: A bear coming towards you in a direct, determined way, with its head low and eyes locked on you, is showing predatory behaviour. This is the most dangerous scenario and demands an immediate, decisive response.

Interpreting these signals correctly tells you what to do next. A curious bear might be scared off by loud noises, whereas a stressed bear needs more space. This is where professional training, like the skills covered in our winter expedition experience , turns from theory into life-saving practice.

The Correct Use Of Deterrents

If an encounter is unavoidable, the professional protocol is a tiered response using the right deterrents. The goal is always to scare the bear away without hurting it. A firearm is the absolute last resort, only used to protect human life when everything else has failed.

The hierarchy of deterrents usually goes like this:

- Voice and Noise: First, make your presence known. Stand tall, make yourself look big, and use a firm, loud voice. Bang pots together or use an air horn. You want to show the bear you are not prey.

- Signal Flares and Pen Flares: If noise does not work, a flare pistol or pen flare fired into the air can be a powerful deterrent. The bright light and sharp crack are often enough to frighten a bear away.

- Bear Bangers: These are pyrotechnics fired from a launcher that explode with a loud bang. They should be aimed to go off between you and the bear, never directly at it.

Each of these tools requires a steady hand and practice. Making clear decisions under the immense pressure of a bear encounter is a skill that must be rehearsed. As you plan your trip and think about safety protocols, do not forget the practicals, like ensuring you have reliable connectivity. You can find helpful information and eSIM options for Canada to stay connected in remote areas.

Ultimately, safety in the Arctic comes down to a mindset. It is a commitment to meticulous preparation, constant awareness, and a profound respect for the power of the environment and its inhabitants.

Preparing For The North With Professional Training

Knowing the facts about polar bears in Canada —their biology, behaviour, and conservation status—is one thing. Turning that knowledge into disciplined action when you're out on the ice is something else entirely.

This is the real work. Travelling safely in the Arctic is not some abstract idea. It is a craft, built on a foundation of specific skills practised until they become instinct.

An expedition is not just about getting to a place on a map. It is about having the deep competence to operate safely and with respect in an environment that demands both. This takes more than just being fit. It demands mental toughness, meticulous daily routines, and the ability to think clearly when the weather closes in and the pressure is on.

Building Expedition Competence

The very skills that keep you safe in polar bear country are the same ones that define any successful polar journey. These are not qualities you are born with; they are learned, honed through practice until they feel like second nature.

The core disciplines are straightforward:

- Navigation and Route-Finding: The ability to read a landscape, to trust a map and compass in a total whiteout, and to understand the subtle language of sea ice.

- Cold-Weather Camp Craft: Mastering the small, vital tasks that keep you going. Efficient tent routines, operating a stove to melt snow for water, and managing your layers to prevent the first chill of hypothermia. These details preserve your energy and focus.

- Mental Fortitude: Learning to manage deep fatigue, keep team morale high, and know the difference between being determined and just being stubborn. In the end, the mental game is often what separates success from failure.

These skills are all woven together. A well-run camp eliminates stress, which frees you up to make better decisions if a bear wanders into view. Trusting your layering system means you are not distracted by the cold, allowing you to focus completely on navigation.

This is how true competence is built—layer by layer, skill by skill.

True exploration is built on respect, and respect is born from understanding. We do not seek to conquer the North; we aim to understand its rhythms and our place within them. This ethos transforms a simple trip into a meaningful journey.

This approach is not just for a single adventure. It gives you a mindset and a toolkit for a lifetime of responsible travel in the world’s last wild places. It is about earning your place in the landscape through preparation and skill.

For those ready to build this foundation, our expedition training course provides the essential framework for any serious northern journey.

Your Questions About Polar Bear Country, Answered

Over the years, we have been asked just about everything when it comes to travelling in the polar bear's world. Here are a few of the most common questions, with answers drawn straight from our field experience.

When Is The Best Time To See Polar Bears In Canada?

For the classic, iconic shots of bears on the tundra, you cannot beat October and November in Churchill, Manitoba . This is when the bears gather on the shores of Hudson Bay, waiting for the sea to freeze over. It is an incredible spectacle and makes them highly visible from the safety of specialised tundra vehicles.

If you are after a rawer, more remote expedition, then spring is your window. From March to May in Nunavut, you have the chance to see mothers emerging with their new cubs, a truly unforgettable sight out on the sea ice.

Just How Cold Will It Be?

In Churchill during the autumn, you should be prepared for temperatures anywhere from -5°C down to -25°C (23°F to -13°F). And that is before the wind. The wind chill can make it feel substantially colder, cutting right through you if you are not properly kitted out.

Spring expeditions in the high Arctic are a different level of cold. Temperatures often drop below -30°C (-22°F). A proper layering system, using a combination of Fjällräven base layers and appropriate outer shells, is not just a good idea—it is absolutely essential for your safety and well-being.

Is It Dangerous To See Polar Bears In The Wild?

Let us be direct: any travel in polar bear territory has risks. But these are risks that can be professionally managed with the right training, discipline, and respect.

The danger is hugely reduced when you travel with experienced guides, keep an obsessively clean and secure camp, and know exactly how and when to use deterrents. The key is prevention and avoidance , not confrontation. We treat these animals as the powerful apex predators they are. That respect is the very foundation of travelling safely in their home.

How Close Can We Get?

Responsible wildlife viewing is all about observation without disturbance. In Churchill, the large tundra vehicles give you a fantastic, elevated view, allowing you to get surprisingly close without ever encroaching on a bear's personal space.

Out on a ground-level expedition, a minimum distance of 100 metres (330 feet) is a standard rule of thumb, but that can change in an instant depending on the terrain, the wind, and the bear's behaviour. The goal is always the same: to watch them in their natural state, completely unaltered by our presence.

At Pole to Pole , we know that a successful expedition is built long before you step onto the ice. It is about building the skills, the mindset, and the deep respect needed to travel with competence in the world's most demanding environments.

Explore our expedition training programmes to start your own journey.